FeederWatchers report fewer crows and chickadees in West Nile virus-infected areas as bird-counting season nears

By Allison Wells

In West Nile virus-afflicted parts of the country last winter, counts of American crows dropped to a 15-year low. Other species, including chickadees, also were scarce, but some species appeared in record-high numbers.

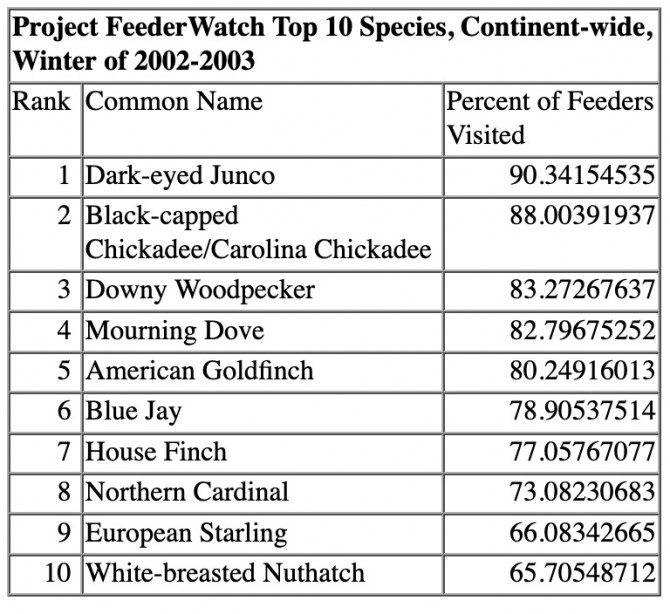

The reports come not only from scientists in the field but from the 16,000 volunteer citizen-scientists in Project FeederWatch who count birds that visit their feeders each winter and send information to Cornell University scientists at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. There, the FeederWatchers' reports are collated and analyzed to determine the status of North America's feeder birds.

"Thanks to the careful reports of these dedicated volunteers, we've been able to make some interesting observations concerning the whereabouts of birds across the continent," says David Bonter, who directs Project FeederWatch. "Findings from last winter are particularly interesting."

Bonter notes that the winter of 2002-03 was one of extremes. American crow counts fell to a 15-year low in the Midwest (Kentucky, Illinois, Indiana and Ohio), a region hard hit by West Nile virus (WNV. Despite this decline, the continentwide abundance of crows continued to be stable.

Not so for other species. In their respective ranges, numbers of black-capped and Carolina chickadees – among the most familiar and beloved bird species – also fell to a 15-year low. "Counts were 15 percent lower this year than last and down 18 percent compared with the previous 14-year average," says Bonter. He adds that chickadees in the Midwest were especially scarce – their numbers were 32 percent lower than their historic FeederWatch average.

However, scientists aren't jumping to conclusions just because the Midwest showed the most dramatic drop in chickadee numbers – and was a WNV hotspot, with a high number of human cases reported last year. Wesley Hochachka, assistant director of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology's Bird Population Studies department and a data analyst for Project FeederWatch, cautions that little is known about how WNV has affected chickadees and most other birds. "Chickadee declines were not limited to states with West Nile virus outbreaks," says Hochachka. "This suggests that the drop in numbers might be attributable to more than just West Nile virus."

Further evidence against a WNV connection is that the declines were not sudden, but rather follow a trend that began in 1998 and hit low points in 2001 and 2003. WNV has only become widespread in North America in the past two years.

House finch numbers also declined last winter. This decline follows a decade-long fall that can be tracked to a bacterial infection that began affecting house finches in the early 1990s. This disease often leads to blindness and death and tends to keep flocks of house finches small. However, when Hochachka and his colleagues closely tracked the movements of the disease, they found that the occurrence of the infection was not abnormally high last winter, leaving the researchers to conclude that factors yet to be determined likely contributed to house finch declines.

FeederWatch did find an increase in some species last winter. For example, both Cooper's hawk and sharp-shinned hawk counts were at an all-time high. These birds of prey are relatively easy to track because they regularly visit feeders, where they dine on smaller birds. Why the increase in their numbers? Many possibilities exist, but Bonter and Hochachka theorize populations could still be rebounding from the decimation caused by the use of the pesticide DDT in the last century.

"It's truly amazing what we've learned from the remarkable dataset provided by Project FeederWatch," says Bonter. "And to think that it exists solely because so many people are willing to take a little time to tell us which birds are visiting their bird feeders through the winter, which makes it more remarkable still. We are truly grateful for their help."

And the ornithologists hope even more citizen-scientists will join FeederWatch for the winter 2003-04 season. Participants receive a research kit that includes instructions, bird-feeding tips, a colorful poster of common feeder birds and a bird-counting days calendar featuring photos taken by FeederWatchers. A $15 fee ($12 for Lab members; $25 for Canadians) helps defray the cost of operating the study.

Information on joining FeederWatch is available toll-free in the United States by calling (800) 843-2473. In Canada the toll-free number for Bird Studies Canada is (888) 448-2473. FeederWatch information also is available at the web site: http://www.birds.cornell.edu/pfw.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe