Noise cuts whale communications in Northeast sanctuary

High levels of background noise, mainly due to ships, have reduced the ability of critically endangered North Atlantic right whales to communicate with each other at the mouth of the Massachusetts Bay by about two-thirds, according to a new study published in the August issue of the journal Conservation Biology (26:4).

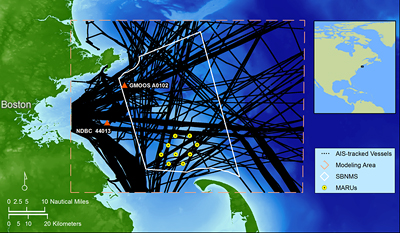

From 2007 until 2010, scientists from the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Northeast Fisheries Science Center and Marine Acoustics Inc. used an array of acoustic recorders to monitor noise levels and measure levels of sound associated with vessels, and to record distinctive sounds made by multiple species of endangered baleen whales, including "up-calls" made by right whales to maintain contact with each other.

The Northeast Fisheries Science Center documented more than 22,000 right whale contact calls as part of the study in April 2008, and software developed by Cornell and Marine Acoustics aided in modeling ship noise propagation throughout the study area.

Vessel-tracking data from the U.S. Coast Guard's Automatic Identification System was used to calculate noise from vessels inside and outside the sanctuary. By further comparing noise levels from commercial ships today with historically lower noise conditions nearly a half-century ago, the authors estimate that right whales have lost, on average, 63-67 percent of their communication space in the sanctuary and surrounding waters.

"A good analogy would be a visually impaired person, who relies on hearing to move safely within their community, which is located near a noisy airport," said Leila Hatch, Ph.D. '04, the sanctuary's marine ecologist and lead author of the paper. "Large whales, such as right whales, rely on their ability to hear far more than their ability to see. Chronic noise is likely reducing their opportunities to gather and share vital information that helps them find food and mates, navigate, avoid predators and take care of their young."

North Atlantic right whales, which live along North America's east coast from Nova Scotia to Florida, are one of the world's rarest large animals and are on the brink of extinction. Recent estimates put the population of North Atlantic right whales at 350 to 550 animals.

"We had already shown that the noise from an individual ship could make it nearly impossible for a right whale to be heard by other whales," said co-author Christopher Clark, director of Cornell's bioacoustics research program. "What we've shown here is that in today's ocean off Boston, compared to 40 or 50 years ago, the cumulative noise from all the shipping traffic is making it difficult for all the right whales in the area to hear each other most of the time, not just once in a while. Basically, the whales off Boston now find themselves living in a world full of our acoustic smog."

The authors suggest that the impacts of chronic and wide-ranging noise should be incorporated into comprehensive plans that seek to manage the cumulative effects of offshore human activities on marine species and their habitats.

The study was funded by the National Oceanographic Partnership Program.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe