'Work first' reforms could ease disability caseloads

By Susan Kelley

More people with disabilities could continue to work, rather than move onto federal benefits, with the help of rehabilitation and accommodations for their disabilities. But current policies prevent them from working to their full capacity, and taxpayers are paying the price, according to a Cornell expert.

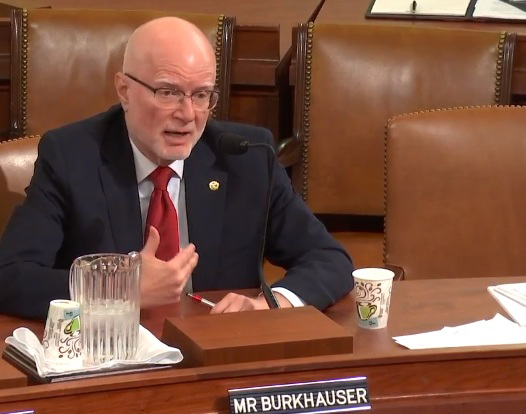

“Fundamental disability reforms can lower long-term costs for taxpayers, make the job of disability administrators less difficult and improve the opportunities of Americans with disabilities to work,” said Richard Burkhauser, the Sarah Gibson Blanding Professor of Policy Analysis in the College of Human Ecology.

Burkhauser delivered this message to lawmakers Nov. 17 during his testimony before the U.S. House Ways and Means Subcommittee on Human Resources in Washington, D.C., at a hearing titled “Moving America’s Families Forward: Lessons Learned From Other Countries.”

He based his testimony on his working paper, “Protecting Working-Age People with Disabilities,” co-authored with Nicholas Ziebarth, assistant professor of policy analysis and management. The paper suggests good news: An increase in benefits for working people with disabilities has more than offset the decline in their earnings over the last 30 years.

The bad news is, to get those benefits, the working disabled must prove they can’t work. “Only after they prove they can’t work do we then systematically try to provide them with help in working. Had many of those on the Social Security Disability Insurance and Social Security Insurance rolls first received accommodation and rehabilitation, they would have not left the labor force in the first place,” Burkhauser said.

He also based his testimony on another working paper, “Measuring Health Insurance Benefits,” co-authored with Jeff Larrimore, Ph.D. ’10, and Sean Lyons, Ph.D. ’14, that reviews three European Union countries – Germany, Sweden and the Netherlands – that have experienced the same growth in their disability rolls that the United States is now experiencing. But the EU countries have initiated “work first” reforms that have slowed the movement of working-age people with disabilities out of employment and onto their disability rolls. “We can do the same here,” Burkhauser said.

One concern is that disability insurance is especially important in economic downturns where individuals with limited work capacity are more likely to be laid off and less likely to find a new job. Past experience, especially in Germany and the Netherlands, which used this logic to turn their long-term disability programs into unemployment programs, suggests that it can be a very expensive and ultimately ineffective policy decision, Burkhauser said. A key message from the EU experience is that explicitly divorcing long-term “unemployability” insurance from disability insurance is critical to effectively targeting resources toward both populations, he said.

“The experiences of E.U. nations suggest that it is possible to balance the competing goals of providing social insurance against adverse health shocks and maximizing the work effort of all working-age adults,” he said.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe