Engaged art and its critique at Cornell

By Linda B. Glaser

Artists today engage with a world very different from that of their predecessors: globally connected, technologically advanced and highly diverse. In the last 50 years the Western canon has been displaced as the benchmark for “good” and worthwhile art, opening the door to works intended to challenge viewers, rather than simply to aesthetically please.

“It’s an exciting time to be an artist,” says Iftikhar Dadi, M.A. ’01, Ph.D. ’03, associate professor of history of art and interim director of the South Asia Program. “A lot of contemporary art is very provocative, pointing us at things that we need to look at but we don’t always.”

Cornell faculty are engaged in the creation of contemporary art as well as in its study and curation. Because contemporary art mediums are limited only by the artist’s imagination and have become unbounded by geographical borders, the wide range of cultural expertise at Cornell lends an important depth to the study of contemporary art. Visual artists today even engage with the boundedness of time, in different forms of performance media.

“Art mediates between thought and the world, between intellectual work and politics and society,” says Pedro Erber, associate professor of Romance studies. “Making art, because of its material aspect, becomes a possible bridge, a way to materialize theory and make it have a presence in the world. When you make something, when you go from thought to a material object, you are dealing with a completely different kind of communication than in academic literature.”

Says Dadi: “Contemporary art doesn’t give you easy solutions. It makes you think in more complex, less instrumental ways and identifies things to which you should be attentive. It offers ways of thinking and experiencing that go beyond established norms, and that’s its value.”

His own work, created with his partner, Elizabeth Dadi, is a good example of this. “Efflorescence,” the Dadis’ recent project, uses the language of pop art and commercial signage in a large-scale commentary on sovereignty and the nation-state: The series consists of six giant industrially fabricated neon flowers, each the national symbol of a country or region with disputed borders.

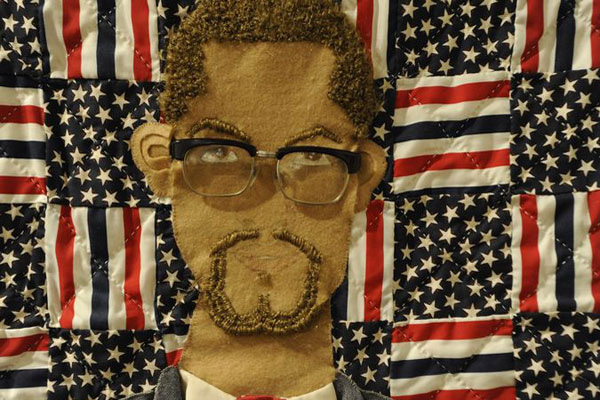

As Bill Gaskins, visiting associate professor in the Department of Art, points out, “It’s redundant to say art and politics. Art is politics.”

Landscape paintings would seem to be a fairly straightforward form, yet from an indigenous perspective, the genre is one of the conceptual and visceral tools of colonization, says Jolene Rickard, associate professor of history of art and director of the American Indian and Indigenous Studies Program. “The representation of the land is a central trope in indigenous thought and visual culture, yet historically, it does not conform to the conventions of art historic painterly or sculptural representations of the landscape. It expresses a very different temporal and philosophical relationship to place.” Suspending the notion of landscape as a painted canvas is appropriate in this context, says Rickard, in which glass chalk beads and blue woolen trade cloth on the bottom corner of a woman’s skirt constitute a Haudenosaunee “landscape.”

Salah Hassan, the Goldwin Smith Professor of African and African Diaspora Art History and Visual Culture, says: “The field of art history itself has moved away from a Eurocentric linear model toward a more global one of studying art movements and artists, and in the process it incorporates new methodologies engendered by imperatives of race, gender, sexualities and other intersectionalities that truly define our world. The field has also moved away from linear narratives of art history that center on the West toward a more comparativist global approach in the study of modernism and modernity.”

Ananda Cohen Suarez, assistant professor of history of art, has found a kind of contemporary art form in historic murals in Peru. “They’re living monuments,” she explains. “Even though we don’t think of them as contemporary art, they’re still interfacing with a contemporary public. These historical images of past struggles resonate with audiences in the contemporary moment.” Her forthcoming book, “Heaven, Hell and Everything in Between: Murals of the Colonial Andes” details her findings.

Linda B. Glaser is a staff writer for the College of Arts and Sciences.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe