Primordial galaxy bursts with starry births

By Blaine Friedlander

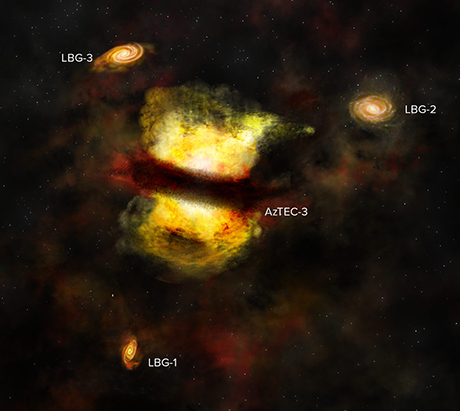

Peering deep into time with one of the world’s newest, most sophisticated telescopes, astronomers have found a galaxy – AzTEC-3 – that gives birth annually to 500 times the number of suns as the Milky Way galaxy, according to a new Cornell-led study published Nov. 10 in the Astrophysical Journal.

Lead author Dominik Riechers, Cornell assistant professor of astronomy, and an international team of researchers gazed back – with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile – over 12.5 billion years to find bustling galaxies creating stars at a breakneck rate. Today, Earth’s Milky Way galaxy produces the equivalent of perhaps two to three new suns a year. The AzTEC-3 galaxy, observed to be emerging from the Big Bang’s primordial soup, creates about 1,100 suns a year, corresponding to about three suns each day.

ALMA’s remarkable sensitivity and spatial resolution was key to observe this galaxy and others with unprecedented detail in far-infrared/submillimeter wavelength light. It also found, for the first time, star-forming gas in three additional, extremely distant members of an emerging galactic protocluster, which is associated with AzTEC-3.

“The ALMA data reveal that AzTEC-3 is a very compact, highly disturbed galaxy that is bursting with new stars at close to its theoretically predicted maximum limit and is surrounded by a population of more normal, but also actively star-forming galaxies,” said Riechers. “This particular grouping of galaxies represents an important milestone in the evolution of our universe – the formation of a galaxy cluster and the early assemblage of large, mature galaxies.”

Riechers says that galaxies with this quick rate of star production have been known to exist in the middle-aged universe, say 3 billion to 6 billion years old, but this production is surprising for galaxies in their cosmic infancy. “We expect this out of later galaxies in a more mature universe, but not from one of the earliest,” he said.

In the early universe, starburst galaxies like AzTEC-3 formed stars at a frenetic pace, fueled by the copious quantities of material they devoured and by merging with other adolescent galaxies. Over billions of years, according to the National Radio Astronomy Observatory, these galactic mergers continued, eventually producing the large galaxies and clusters of galaxies seen in the cosmos today.

“One of the primary science goals of ALMA is the detection and detailed study of galaxies throughout cosmic time,” said Chris Carilli, an astronomer with the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in Socorro, New Mexico. “These new observations help us put the pieces together by showing the first steps of a galaxy merger in the early universe.”

The astronomers believe that AzTEC-3 and the other nearby galaxies appear to be part of the same system, but are not yet gravitationally bound into a clearly defined cluster. This is why the astronomers refer to them collectively as a protocluster. “AzTEC-3 is currently undergoing an extreme, but short-lived event,” said Riechers. “This is perhaps the most violent phase in its evolution, leading to a star formation activity level that is very rare at its cosmic epoch.”

ALMA is a group of radio telescopes partially managed by the National Radio Astronomy Observatory. It obtains funding internationally, including from the National Science Foundation.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe