Larger, adjustable computer mouse could reduce risk of wrist injury, Cornell study finds

By Susan S. Lang

An oversized, flatter and adjustable computer mouse with built-in palm support could lower the risk for carpal tunnel syndrome and other wrist injuries, according to a new study by Cornell University ergonomists.

The study found that the new mouse allows computer users to keep twice as many of their wrist movements in a neutral, low-risk zone compared with a traditional, small mouse.

"More than half of all hand movements with the oversized, flatter mouse stay in a neutral zone, compared with only one-quarter of the movements with a traditional mouse," says Alan Hedge, professor of design and environmental analysis at Cornell and director of Cornell's Human Factors and Ergonomics Laboratory. These findings were consistent for tall, average and small men and women.

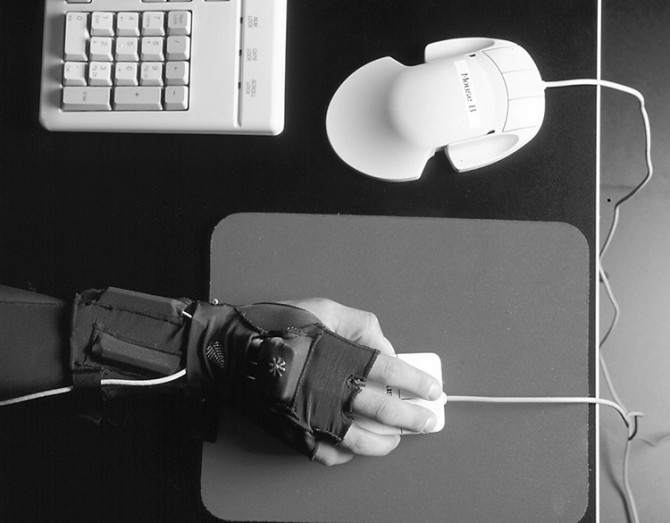

Assisted by graduate students Timothy M. Muss and Marisol Barrero, Hedge analyzed the wrist extension and hand movements of 24 men and women performing mouse tasks involving cursor position and scrolling. Subjects wore a right-hand instrumented glove to measure wrist posture; the researchers also analyzed task performance, and the subjects rated the comfort and usability of the larger devices. The keyboard and mouse were both placed on a flat keyboard tray beneath desk height; the mouse surface was located approximately at seated elbow height.

The ergonomists found significant differences between the large and small mouse designs for wrist extension; on average, the larger mouse reduced wrist extension by an average of more than eight degrees.

"Use of a computer mouse is not necessarily benign. Evidence is mounting that computer mouse use is associated with a number of upper extremity musculoskeletal disorders," says Hedge. He points out that in 1988 not a single workers' compensation claim form in the United States reflected computer-related cumulative trauma disorders of the upper extremity associated with mouse use. By 1993, the number had soared to 325,000. Of those, 51 percent involved wrist injury.

"Our data suggests that an oversized, flatter mouse with palm support can be effective in encouraging users to perform more of their mouse work with the hand in a neutral posture," Hedge says.

Although both mouse designs were contoured to improve neutral wrist posture, the larger mouse was flatter as well as adjustable, discouraging small hand movements, such as flicking of the wrist, which could exacerbate injury risks, Hedge says. This mouse's large movable sleeve also allowed the user to adjust to different hand sizes and served as a built-in wrist support.

Hedge points out that although the time it took users to perform the tasks was 19 percent longer with the larger mouse, this was a short-term test and users were unfamiliar with the design and the difference would probably diminish with more practice.

"Future studies should look at longer term use and how the mouse affects the whole arm and upper body posture," Hedge says. "Also, previous research suggests that the mouse location in our study, to the right of the keyboard, was not optimal. We think we would see even stronger results if the larger, flatter mouse were on a mouse tray 20 percent above seated elbow height and closer to the midline of the body."

The study has been published as Cornell Human Factors Laboratory Technical Report RP7992 and can be accessed on the World Wide Web at http://ergo.human.cornell.edu/CUHFdownmouse.html.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe