Cornell researchers' probe discovers pollutant-eating microbe and a strategy to speed cleanup of old gasworks

By Roger Segelken

ITHACA, N.Y. -- Cornell University microbiologists, looking for bioremediation microbes to "eat" toxic pollutants, report the first field test of a technique called stable isotopic probing (SIP) in a contaminated site. And they announce the discovery and isolation of a bacterium that biodegrades naphthalene in coal tar contamination.

Although naphthalene is not the most toxic component in coal tar, the microbiologists say their discovery might eventually help to speed the cleanup of hundreds of 19th and 20th century gasworks throughout the United States where the manufacture of gas from coal for homes and street lighting left a toxic legacy in the ground.

The National Science Foundation-funded research is reported in the online edition of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS early edition, Oct. 27, 2003) by researchers working at the NSF Microbial Observatory at Cornell.

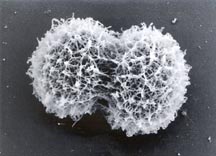

The naphthalene-eating bacterium, Polaromonas naphthalenivorans strain CJ2, was discovered in a 40-year-old municipal gasworks coal tar disposal site in South Glens Falls, N.Y., near the west bank of the Hudson River.

"Strain CJ2 alone won't solve the coal tar problem because naphthalene is only one of the many organic chemicals involved. That's why we're going back to look for other microorganisms -- perhaps with similar gene sequences -- that might be biodegrading other toxins," says the article's lead author, Eugene L. Madsen, associate professor of microbiology in Cornell's College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. He says that naphthalene's carcinogenic relatives in coal tar, known as polycylic aromatic hydrocarbons, are toxins that his research group hopes to degrade.

The use of SIP to identify pollutant-eating microbes is something like using the milk-mustache test to discover which child drank the milk. In the first successful field application of SIP in a contaminated site, the microbiologists released into the Hudson River coal tar waste a small amount of naphthalene-containing carbon-13, a stable isotope of carbon. Then they looked for two types of "milk-mustache evidence" proving that the naphthalene was being processed by microorganisms. Part of this evidence was that the bacteria in the sediment produced carbon dioxide (CO2) labeled with carbon-13. In addition, the same bacteria incorporated carbon-13 into their nucleic acids. After extraction of nucleic acids from the sediment, DNA testing revealed a signature DNA sequence for the bacteria responsible for biodegrading the naphthalene. Subsequently, the researchers were able to isolate from the sediment and grow a previously unknown naphthalene-degrading bacterium with a matching DNA signature. The microbiologists then grew the bacterium, dubbed CJ2, and added it to the coal tar sediment samples, where the microorganism accelerated the loss of naphthalene.

The harnessing of CJ2 is related to the 1997 discovery by Cornell microbiologists of a bacterium (Dehalococcoides ethenogenes ) that biodegrades the industrial cleaning compound trichlorethylene (TCE). Billions of D. ethenogenes microbes are now at work at a New Jersey Superfund site and other TCE-polluted locations.

"D. ethenogenes was discovered, almost accidentally, before we had the advantage of stable isotopic probing," Madsen observes, "Finding the bugs actually responsible for biodegradation processes among the millions of known and unknown species out there is always difficult, but we've shown that SIP makes the search a little easier." The SIP strategy had been tested before in the laboratory and in agricultural plots but never before in a genuine contaminated field site.

Other authors of the PNAS article, "Discovery of a novel bacterium, with distinctive dioxygenase, that is responsible for in situ biodegradation in contaminated sediment," include: Che Ok Jeon, currently a research scientist at the Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology; Woojun Park and Christopher DeRito, Cornell graduate students; P. Padmanabhan, research scientist at the National Environmental Engineering Research Institute, India; and J.R. Snape, senior microbiologist, AstraZeneca, England.

The research was conducted with cooperation from Niagara Mohawk Power Corp. and the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation.

Related World Wide Web sites: The following sites provide additional information on this news release. Some might not be part of the Cornell University community, and Cornell has no control over their content or availability.

o NSF Microbial Observatory at Cornell:

http://www.micro.cornell.edu/NSF.Observatory.htm

o News about the Microbial Observatory:

http://www.news.cornell.edu/releases/Feb02/microbial_observatory.hrs.html

-30-

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe