Millipede's 'barbed grappling hooks' thwart predators, scanning electron microscope study reveals

By H. Roger Segelken

Microscopic examination has revealed the defense secret of a tiny millipede that was entangling its enemies millions of years before porcupines and Velcro came along.

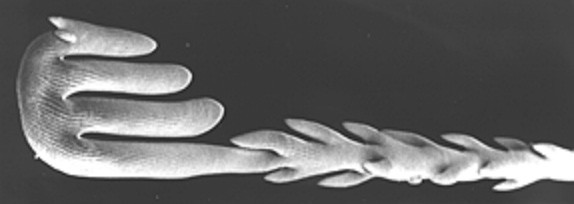

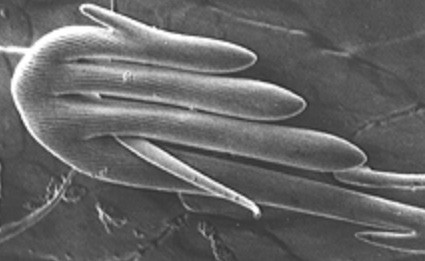

As reported in the Oct. 1 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) by Thomas Eisner, Maria Eisner and Mark Deyrup, the millipede Polyxenus fasciculatus confronts ants and other attackers with its rear. Located there are brush-like tufts of detachable bristles with a horrible surprise for the predators: multipronged grappling hooks at the bristle ends to latch onto hairlike setae of the attacking insects and barbs along the shafts to link the bristles in an often-inescapable mesh.

"The ant's first reaction to this insult is to preen. That's what it would do to get rid of a defensive chemical," said Thomas Eisner, the Schurman Professor of Biology at Cornell University and a specialist in the chemical ecology of insects. "But preening only makes matters worse for the ant. This is a mechanical defense, a cross between the quills of the porcupine and the hooks and loops of Velcro -- a very unforgiving Velcro. The more the ant preens and struggles, the more entangled it becomes."

In the past, Eisner and his colleagues at the Cornell Institute for Research in Chemical Ecology (CIRCE) have successfully explained the chemical defense strategies of dozens of insects, millipedes and other arthropods. And he was puzzled at first to learn that the P. fasciculatus millipede had survived so long without chemistry on its side. "These may be among the oldest millipedes on Earth, dating to the Silurian period when animals first colonized the land," he said. "One defensive strategy is to change your habitat, but P. fasciculatus haven't; they have held their own among some very persistent predators, particularly ants."

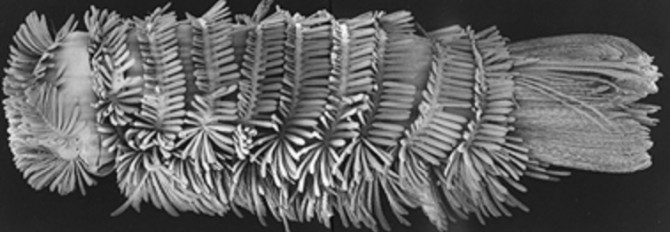

When Deyrup, a staff scientist at the Archbold Biological Station in Lake Placid, Fla., found P. fasciculatus millipedes under the loose bark of slash pines as well as Crematogaster ashmeadi ants foraging nearby, Eisner enlisted the help of a highly skilled scanning electron microscopist -- his wife. Together with Maria Eisner, a research associate at CIRCE, he brought ants and millipedes face to face. When the millipedes turned tail, splayed the bristle tufts and briefly stroked the attacking ants, it was scanning electron microscopy (SEM) that revealed the mechanics of a near-perfect defense.

The bristles -- so minute that standard light microscopes at lower magnification can barely resolve them -- turned out to be complex structures under SEM examination and photography. Tiny barbs, sharper than any fish hook, cover the shafts of the bristles. At each bristle end is a three-pronged hook to clench the body hairs of other insects. Maria Eisner's SEM images show the perplexed ants, immobilized by an interlocking mesh of millipede bristles.

Worse yet (for the predators), the porcupine-Velcro millipedes have enough bristles to repulse several attacks, the Cornell experiments showed. And if P. fasciculatus are anything like a closely related millipede species, P. lagurus, their bristles are renewable when they molt.

The bristle-baring millipedes are not the only arthropods with a mechanical advantage, the biologists observe in their PNAS article. Tarantulas use their legs to flick the loose hairs on their backs toward predators. And some caterpillars are protected by stinging hairs, which they also use to impregnate their cocoons when they pupate.

Detachable bristles seem like a perfect defense, and they are -- almost, Thomas Eisner noted. But there is one Brazilian ant in the Thaumatomyrmex genus that was known to cope with bristle millipedes by grabbing them with its specialized mandibles, killing the prey with a sting, stripping them of their bristles, before finally eating the millipedes.

"That's life in the natural world," Eisner commented. "For every strategy, no matter how 'perfect,' there is a counter-strategy."

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe