Gene therapy restores vision to dogs blinded by inherited disease, bringing new hope to childhood sufferers of similar condition

By H. Roger Segelken

Dogs blinded by an inherited retinal degenerative disease had their vision restored after treatment with genes from healthy dogs, marking the first successful gene therapy for blindness in a large animal. The treatment offers hope for humans with a similar condition.

The achievement, with young dogs suffering from congenital stationary night blindness, which is similar to a childhood disease called Leber congenital amaurosis, is reported in the May 2001 issue of the journal Nature Genetics by Gregory M. Acland, Gustavo D. Aguirre, Jharna Ray, Qi Zhang and Susan E. Pearce-Kelling, all at the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine; by Tomas S. Aleman, Artur V. Cideciyan, Vibha Anand, Yong Zeng, Albert M. Maguire, Samuel G. Jacobson and Jean Bennett, all at the University of Pennsylvania; and by William W. Hauswirth of the University of Florida, Gainesville.

"We have shown that gene therapy can restore vision in dogs with one of the most clinically severe retinal degenerations," says Acland, a research veterinarian at Cornell's James A. Baker Institute for Animal Health. "Many safety and efficacy studies must be performed before we can begin clinical trials, but this [gene therapy] could correct defects in humans with RPE65 mutations," Acland says. RPE65 is a gene associated with the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE).

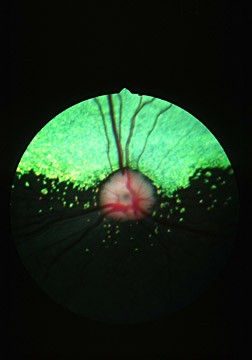

The RPE cell layer in the eyes of humans, dogs and other mammals supports the retina by providing nourishment and removing waste products while supplying vitamin A to the photoreceptors. Puppies and human infants with defective RPE65 genes produce a mutant form of the RPE65 protein, resulting in early vision loss, degeneration of the retinas and near-total blindness later in life. The canine form of this retinal degenerative disease has been found only in the briard dog breed. In the gene therapy experiments, researchers used RPE65 genes that were cloned from dogs without the disease, together with a viral vector (recombinant adeno-associated virus, or AAV) to carry the normal dogs' DNA. They injected the combination into the subretinal space of the eyes of 3-month-old briard-beagle mix dogs that were known to have the defective RPE65 gene and had been blind since birth. Within six weeks, the treated eyes were producing the correct form of RPE65 protein. By three months, a series of tests (electroretinography, pupillometry and obstacle-avoidance tests in a dimly lit room) demonstrated that vision was restored to the treated eyes.

"This is a perfect example of how research in animals helps both the animal -- in this case the dog -- and the human patient," says Aguirre, who is the Caspary Professor of Ophthalmology at Cornell and whose laboratory discovered the RPE65 gene defect in briard dogs in 1998.

Since then, DNA tests developed at Cornell are allowing breeders of briard dogs to screen for the defective RPE65 gene and, by selective breeding, essentially to eliminate congenital stationary night blindness in the canine population outside the laboratory. "Regardless of how successful the treatment has been for dogs, it is essential that more studies are carried out to establish the long-term safety and efficacy of gene therapy for human patients," Aguirre adds.

Previous experiments had used gene therapy to slow degeneration of retinas in mice, but the treatment reported in Nature Genetics is believed to be the first cure for retinal degenerative disease in a "large animal."

Jacobson, the director of the Center for Hereditary Retinal Degenerations at Pennsylvania's Scheie Eye Institute, says the gene therapy study in dogs "signals that the time has finally arrived to stop theorizing about treatment for these devastating human eye diseases and to start preparing seriously. We will now be assessing patients who could potentially benefit from this discovery."

At the F.M. Kirby Center for Molecular Ophthalmology in the Scheie Institute, Bennett says, "We have worked hard for many, many years trying to develop a treatment for retinal degeneration, and this is the biggest leap forward yet. The results will expand the possible treatment strategies for a diverse set of retinal diseases."

She attributes the gene therapy achievement to "an exceptional and talented group of investigators" at the Retinal Disease Studies Facility, a resource managed by the investigators on behalf of Cornell for various canine breeds with different forms of inherited blindness. Bennett also credits Hauswirth, a member of the University of Florida's Department of Ophthalmology and Powell Gene Therapy Center, for designing the viral vector used in the experiments. Whatever the future holds for human patients with retinal degeneration, gene therapy for dogs with the RPE65 defect is not likely to be performed on a routine basis, Acland says. For one thing, the procedure would be prohibitively expensive to dog owners and must be performed during a narrow window of opportunity before puppies' retinas are destroyed by the disease. "And, thanks to the RPE65 gene test -- and to selective breeding of dogs, an ethical option we do not have in humans -- this is well on its way to becoming a non-disease in dogs."

However, Aguirre adds, "as medical advances are made both in human and veterinary medicine, "treatments such as gene therapy, which now are done on an experimental basis in both animals and man, will likely become accepted treatment modalities in both species."

Acland, Maguire and Jacobson will give more details of the gene therapy procedure and discuss possible treatments for human patients May 1 in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., at the annual meeting of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology. The studies were funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health and The Foundation Fighting Blindness.

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe