A campus takeover that symbolized an era of change

By George Lowery

The first in a series of articles about the four-decade legacy of the 36-hour student takeover of Willard Straight Hall that began April 18, 1969.

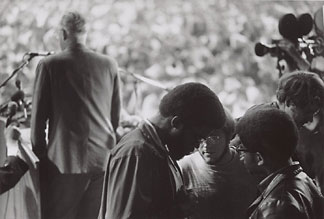

Early in the morning of Parents' Weekend, 40 years ago this Saturday, 11 fire alarms rang out across the Cornell campus. At 3 a.m., a burning cross was discovered outside Wari House, a cooperative for black women students. The following morning, members of the Afro-American Society (AAS) occupied Willard Straight Hall to protest Cornell's perceived racism, its judicial system and its slow progress in establishing a black studies program.

The events that were to prompt decades of social, cultural and political change on campus were in play.

At 9:40 a.m., in an attempt to take the building back, white Delta Upsilon fraternity brothers entered the Straight and fought with AAS students in the Ivy Room before being ejected. Fearing further attacks, the black students brought guns into the Straight to defend themselves.

On the evening of April 19, in freezing rain, rookie Cornell police officer George Taber patrolled the perimeter of the occupied Willard Straight Hall unarmed. Members of Students for a Democratic Society -- students far to the left of many of the black students inside -- formed a ring around the Straight to lend support.

Today, Taber recalls the period as "a whirlwind. One thing after another. I was a raw rookie. I had no idea what was going on."

Within hours, police deputies from Rochester, Syracuse and across New York state massed in downtown Ithaca. "Had they gotten the command to do so, they would have gone and taken the Straight back and arrested people, or who knows what would have happened. It could have made Kent State and Jackson State look like the teddy bear's picnic. It would have been just absolutely terrible," Taber reflects.

On Sunday afternoon, following negotiations with Cornell officials, the AAS students emerged from the Straight carrying rifles and wearing bandoleers. Their image, captured by Associated Press photographer Steve Starr, in a Pulitzer Prize-winning photo, appeared in newspapers across the country and on the cover of Newsweek magazine under the headline, "Universities Under the Gun."

Although physical disaster was averted, deep psychological scars burned into the minds of many on campus. Four decades later, feelings in some quarters are still raw. The university as a bastion of reasoned argument, thoughtful debate and academic freedom seemed to be under siege. Relationships among faculty members were destroyed. Students were torn. An atmosphere of pervasive fear and anxiety gripped the campus and the nation. The AAS students were not punished, outraging some faculty members, students and alumni.

Within Cornell, the takeover has come to be seen as an event that gave birth to enormous social, governance and ideological change. In fact, institutional change was already under way.

In 1963, his first year in office, Cornell President James Perkins had launched the Committee on Special Educational Projects (COSEP) to increase enrollment of African-American students at Cornell and provide them with support services -- the first program of its kind at a major American university.

Perkins, who had chaired the board of trustees of the United Negro College Fund, said Cornell wanted to "make a larger contribution to the education of qualified students who have been disadvantaged by their cultural, economic and educational environments." COSEP later expanded to include Latino and Hispanic American, Native American and Asian-American students.

Only days before the Straight takeover, on April 10, 1969, the Cornell administration had approved $240,000 to create an Afro-American Studies Center and a director, James Turner, had been identified months earlier. "The students wanted an autonomous program; they wanted the center to have control of its own destiny," said Eric Acree, librarian at the Africana Studies and Research Center.

But change did come even more quickly after the takeover. "You now have recognition that other people need to be studied -- women, gays and lesbians, Latinos, Asian Americans -- and all of that is an outgrowth of the black studies movement," said Acree.

According to Robert L. Harris, professor of Africana studies, entire scholarly fields had been ignored. "The seriousness of Africana studies as an academic endeavor had been questioned, simply because the breadth and depth of existing scholarship was not widely known," he said. "In the decades since, the field has been the source of vast quantities of indisputably serious, relevant, compelling work."

As the academic canon broadened, so did student living options with the establishment of Ujamaa Residential College in 1971, followed by Akwe:kon in 1991 and the Latino Living Center in 1994. The current home of the Africana Studies and Research Center opened in 2005 (the first center was destroyed by arson in 1970). Students and staff now serve on the Cornell Board of Trustees. The university's need-blind admissions policy and Student Assembly can also be traced to the takeover. And only this year, an Asian and Asian-American student center was approved.

Perkins resigned at the end of the semester after the takeover, and for years he was widely regarded as a decent but ineffectual president. But in 1995 Thomas W. Jones, a leader of the takeover, established the James A. Perkins Prize for Interracial Understanding and Harmony, to acknowledge the historic role that Perkins played in changing Cornell.

"President Perkins made the historic decision to increase very significantly the enrollment of African-American and other minority students at Cornell," said Jones at the time. "He did so in the conviction that Cornell could serve the nation by nurturing the underutilized reservoir of human talent among minorities, and in the faith that the great American universities should and could lead the way in helping America to surmount the racial agony which was playing out in the civil rights struggles of the 1950s and 1960s. He made a courageous and wise decision and deserves recognition for it."

The radical ideals Ezra Cornell advanced in 1865 to found his university survived -- though the tumultuous events of the late 1960s forced the university to adapt. But in the end, after a long period of radical change, it has ultimately thrived.

"The whole decade," beginning with the 1963 assassination of President John F. Kennedy, "was a prelude to the takeover," recalls Cornell Dean of Students Kent Hubbell, who was a graduate student in 1969.

There were multiple issues firing the national social cauldron in 1969, in addition to the anti-Vietnam War, civil rights, women's rights and Black Power movements: calls for Cornell to divest itself of investments in South Africa because of apartheid; starvation in Biafra; youth culture; drug culture; the sexual revolution; and, above all, the specter of the draft.

Almost exactly a year before the Straight takeover, on April 23, 1968 -- 19 days before the assassination of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. -- 150 Columbia University students were injured when New York City police violently put an end to black and radical students taking control of five campus buildings in protest of the Vietnam War and racism.

On May 17 of that year, Daniel Berrigan, the Jesuit assistant director of Cornell United Religious Work from 1966 to 1970, along with eight others, entered the Catonsville, Md., Selective Service office and burned dozens of draft records with napalm to protest the Vietnam War. They became known as the Catonsville Nine. Berrigan appeared on the FBI's 10 Most Wanted list.

Also in May, student protests paralyzed France and nearly brought the government down. Eleven days before the Straight takeover, 300 Harvard students, mostly members of Students for a Democratic Society, seized the administration building; 45 were injured and 185 arrested. Even as the Straight takeover occurred, National Guard helicopters sprayed skin-stinging powder on anti-war protesters in California.

In January 1969, six years after the publication of "The Feminine Mystique" and three years after the founding of the National Organization for Women, Betty Friedan came to Cornell to participate in a four-day Conference on Women -- one of the first of its kind to take place on a college campus. That summer would bring the Woodstock Festival, criminal charges against Lt. William Calley for the My Lai Massacre of 109 Vietnamese civilians and ongoing turmoil.

University Archivist Elaine Engst arrived at Cornell in fall 1968 as a graduate student. "It was such a fraught time in so many ways," she said. "Civil rights, the anti-war movement, youth culture. It was a very, very hard time. Studies were interrupted; for two years in a row classes didn't finish in the spring, they just stopped. The campus was basically in a continual uproar."

Posters distributed on campus in 1969 portray a divided era. At the same time as "spring fantasy" semiformals, polo matches and art exhibitions were promoted, there were offers of draft counseling ("Draft got you bugged?") and rallies against ROTC and Cornell's research on behalf of the war -- often in day-glo colors.

And then the Straight was taken over. Within weeks, student uprisings occurred on the campuses of Dartmouth College and Princeton, Tulane and Howard universities. President Perkins, said Engst, "lost control because, like many other university administrators, he really didn't understand the situation or the levels of feeling. Cornell was fortunate to have Provost Dale Corson assume the presidency, with his knowledge and credibility among students and faculty."

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe