Shattering records: Thinnest glass in Guinness book

By Anne Ju

At just a molecule thick, it’s a new record: The world’s thinnest sheet of glass, a serendipitous discovery by scientists at Cornell and Germany’s University of Ulm, is recorded for posterity in the Guinness Book of World Records.

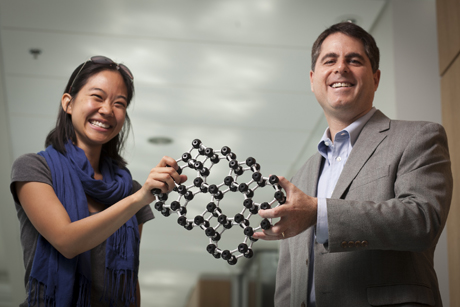

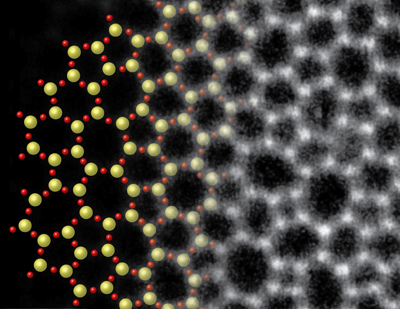

The “pane” of glass, so impossibly thin that its individual silicon and oxygen atoms are clearly visible via electron microscopy, was identified in the lab of David A. Muller, professor of applied and engineering physics and director of the Kavli Institute at Cornell for Nanoscale Science.

The work that describes direct imaging of this thin glass was published in January 2012 in Nano Letters, and the Guinness records officials took note. They published the achievement in early September for inclusion in the 2014 book, and the breakthrough is featured in the publication’s 21st Century Science spread.

Just two atoms in thickness, making it literally two-dimensional, the glass was an accidental discovery, Muller said. The scientists had been making graphene, a two-dimensional sheet of carbon atoms in a chicken wire crystal formation, on copper foils in a quartz furnace. They noticed some “muck” on the graphene, and upon further inspection, found it to be composed of the elements of everyday glass – silicon and oxygen.

They concluded that an air leak had caused the copper to react with the quartz, also made of silicon and oxygen. This produced the glass layer on the would-be pure graphene.

Besides its sheer novelty, Muller continued, the work answers an 80-year-old question about the fundamental structure of glass. Scientists, with no way to directly see it, had struggled to understand it: It behaves like a solid but was thought to look more like a liquid.

Now, the Cornell scientists have produced a picture of individual atoms of glass, and they found it strikingly resembles a diagram drawn in 1932 by W.H. Zachariasen – a longstanding theoretical representation of the arrangement of atoms in glass.

“This is the work that, when I look back at my career, I will be most proud of,” Muller said. “It’s the first time that anyone has been able to see the arrangement of atoms in a glass.”

What’s more, two-dimensional glass could someday find a use in transistors, by providing a defect-free, ultra-thin material that could improve, for example, the performance of processors in computers and smartphones.

The paper, “Direct Imaging of a Two-Dimensional Silica Glass on Graphene,” was published in Nano Letters on Jan. 23, 2012, with first authors Pinshane Huang, a Cornell graduate student, and Simon Kurash, a University of Ulm graduate student. It includes collaborators from the University of Ulm, Germany; the Max Planck institute for Solid State Research in Germany; University of Vienna; University of Helsinki; and Aalto University in Finland.

The work at Cornell was funded by the National Science Foundation through the Cornell Center for Materials Research.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe