Fully functional loudspeaker is 3-D printed

By Anne Ju

Cornell researchers have 3-D printed a working loudspeaker, seamlessly integrating the plastic, conductive and magnetic parts, and ready for use almost as soon as it comes out of the printer.

It’s an achievement that 3-D printing evangelists feel will soon be the norm; rather than assembling consumer products from parts and components, complete functioning products could be fabricated at once, on demand.

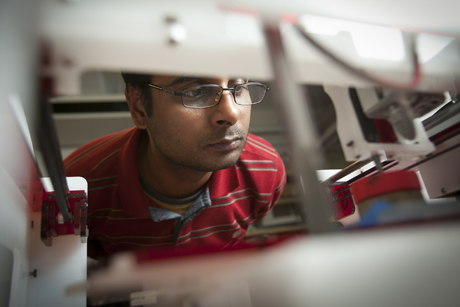

The loudspeaker is a project led by Apoorva Kiran and Robert MacCurdy, graduate students in mechanical engineering, who work with Hod Lipson, associate professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering, and a leading 3-D printing innovator.

“Everything is 3-D printed,” said Kiran, as he launched a demo by connecting the newly printed mini speaker to amplifier wires. For the demo, the amplifier played a clip from President Barack Obama’s State of the Union speech that mentioned 3-D printing.

A loudspeaker is a relatively simple object, Kiran said: It consists of plastic for the housing, a conductive coil and a magnet. The challenge is coming up with a design and the exact materials that can be co-fabricated into a functional shape.

Lipson said he hopes this simple demonstration is just the “tip of the iceberg.” 3-D printing technology could be moving from printing passive parts toward printing active, integrated systems, he said.

But it will be a while before consumers are printing electronics at home, Lipson continued. Most printers cannot efficiently handle multiple materials. It’s also difficult to find mutually compatible materials – for example, conductive copper and plastic coming out of the same printer require different temperatures and curing times.

In the case of the speaker, Kiran used one of the lab’s Fab@Homes, a customizable research printer originally developed by Lipson and former graduate student and lab member Evan Malone, that allows scientists to tinker with different cartridges, control software and other parameters. For the conductor, Kiran used a silver ink. For the magnet, he employed the help of Samanvaya Srivastava, graduate student in chemical and biomolecular engineering, to come up with a viscous blend of strontium ferrite.

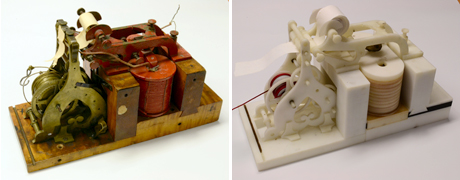

It’s not the first time a consumer electronic device was printed in Lipson’s lab. Back in 2009, Malone and former lab member Matthew Alonso printed a working replica of the Vail Register, the famous antique telegraph receiver and recorder that Samuel Morse and Alfred Vail used to send the first Morse code telegraph in 1844.

Alonso, who was an undergraduate at the time, decided to try to print an electromagnetic device, and Lipson suggested the Vail Register – it was an early application of electromagnetism, and, because Ezra Cornell made his fortune in the telegraph industry, it was also central to Cornell history – “kind of poetic,” Lipson said.

After making a detailed digital model of the telegraph, they printed it on a research fabber also developed by Malone that was a predecessor to the Fab@Home. And it worked. As a demo, the researchers received and printed the same message Morse and Vail first did in 1844: “What hath God wrought.”

Creating a market for printed electronic devices, Lipson said, could be like introducing color printers after only black and white had existed. “It opens up a whole new space that makes the old look primitive,” he said.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe