Cornell Rewind: 'Above all nations is humanity'

By Elaine Engst and Blaine Friedlander

“Cornell Rewind” is a series of columns in the Cornell Chronicle to celebrate the university’s sesquicentennial through December 2015. This column will explore the little-known legends and lore, the mythos and memories that devise Cornell’s history.

Sitting next to Modesto Quiroga at an Ithaca boarding house supper table, a young woman heard his difficulties with the English language. Her own brothers had just returned from the Spanish-American War.

“You are a Spaniard,” she said.

“I, a Spaniard? No,” said Quiroga. “I am an American.”

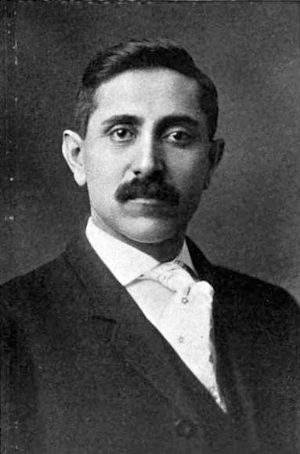

Quiroga – a Cornell graduate student from Argentina – considered himself a world citizen. “His vision took in the whole world,” wrote Thomas Hunt (an agriculture professor, who left Cornell to become Pennsylvania State University’s dean of agriculture in 1907) in the 1906-07 Cosmopolitan Club annual. “[Quiroga’s] philosophy was not circumscribed by any school. He not only had knowledge of world movements and ideas, but understanding, and with it that sympathy that grows out of acquaintance and understanding.”

The idealistic Quiroga embraced national diversity in the highest sense. “Modesto Quiroga is one of those rare spirits who see things in true perspective without local color or prejudice,” explained Hunt.

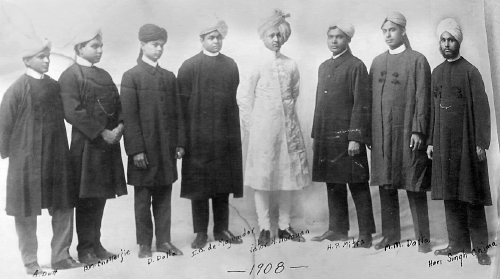

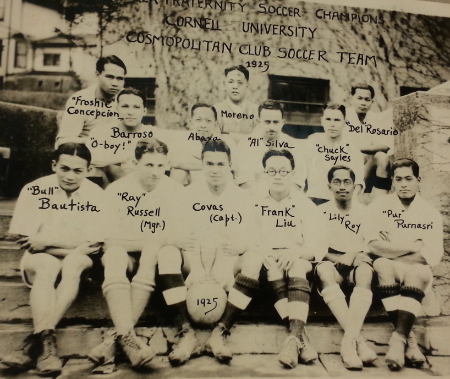

International students had come to Cornell from the beginning of the university, and some foreign students – graduate and undergraduate – and some faculty created social organizations for themselves. In 1873 the Brazilian students published “Aurora Brasileira,” a monthly newsletter written in Portuguese, and established Club Brasileiro. In 1888-89 Latin American students from Nicaragua, Puerto Rico, Honduras and Brazil created Alpha Zeta, a short-lived, so-called “foreigner’s fraternity.” In 1894, a Canadian Club appeared, and a Club Latino-Americano flourished for a time. The Chinese Students Association was founded in 1904; a Filipino Cornellians group began in 1924.

Origins of the Cosmopolitan Club

Organized by Quiroga, Cornell’s Cosmopolitan Club, a group intended for all international students, first met on Nov. 10, 1904, in Barnes Hall, with 60 students attending. Quiroga – along with faculty members Vladimir Karapetoff, engineering professor; George Prentice Bristol, professor of Greek; and Liberty Hyde Bailey, the renowned dean of the newly established New York State College of Agriculture – led the meeting. By the next meeting, weeks later, more than 100 people crammed into tight quarters at the law school in Boardman Hall (now the site of the Olin Library.)

The group initially rented rooms at 313 Eddy St. Cornell President Jacob Gould Schurman and former President Andrew Dickson White were frequent visitors and honorary members of the organization. Countries represented in the early years included Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Bulgaria, China, England, Germany, India, Ireland, Japan, Mexico, the Netherlands, the Philippines, Peru, Romania, Russia, Scotland, South African, Turkey and Sweden.

‘They might find the best in one another…’

In 1911, the club moved into its newly built residence at 301 Bryant Ave., with rooms for 30-40 men, a dining room for 100, and an auditorium seating 400-500. The building was dedicated on Nov. 11, 1911, with a speech by White on “The Hague Conference and the Maintenance of Peace.” While the Cosmopolitan Club ceased operations in 1954, the building remains in Collegetown as a private apartment house.

For five decades, the Cosmopolitan Club would meld international students and elevate peaceful thoughts. Christian Bues, a German undergraduate student, concisely explained the existence of Cornell’s Cosmopolitan Club: “It was founded to bring intelligent thinking men of different nations in such contact that they might find the best in one another; that they might learn to love, to live on common bases side by side; it was founded to make men understand the spirit of nations so that in difficult international conflicts they might have a clear judgment and correct reasoning.”

The club – with the motto “Above all nations is humanity” – became a machine of continuous activity. It was an opportunity for students and professors to illuminate others students about the world. It participated in university activities and held informal summer programs, important for international students who couldn’t travel home for the summer. It also actively promoted the organization of chapters in other universities, since one of its objects was “to promote the organization of chapters in other universities in the United States of America and in other countries.” As early as 1907, there were chapters in Michigan, Wisconsin and Illinois, and a national Association of Cosmopolitan Clubs was founded.

National nights

The group met to discuss “various forms of government now flourishing in the world” or free trade and protection. In 1905 Professor Nathaniel Schmidt gave a talk on “Travelling Experiences in Palestine.” When the 1906 San Francisco earthquake occurred, geological sciences Professor Ralph Stockman Tarr addressed the club. Professor Jeremiah Jenks, history and political science, spoke to the group on the hot topics of immigration and the Chinese boycott of American goods. The club held national nights for China, Japan, Argentina, the Netherlands, Brazil, the British and South Africa.

At the club’s first annual banquet, June 1905, the members dined on little neck clams, consommé royal, baked bluefish a la creole, veal croquettes and Cosmopolitan Punch, all the while listening to a program mixed with Edvard Grieg’s “Solvejg’s Song,” more music by the Cosmopolitan Club Orchestra and a lecture, “The Present Political Situation in Sweden and Norway,” by history Professor Ralph Catterall. He explained the ongoing civil war following Norway’s breakaway from Sweden. “The quarrel between Norway and Sweden was quietly discussed in the peaceful atmosphere of tobacco smoke,” wrote Abraham Abbey Freedlander ’05, in the club’s annual report.

Initially, women were not included in the club, probably reflecting the relatively few women students from other countries and cultural sensitivities. Events including women were held as early as 1906, and a Women’s Cosmopolitan Club was founded in 1921. Thirty years after the men’s club formed, the group’s constitution was amended to include female students.

‘A more human place…’

In 1920, Leonard Elmhirst became president of the Cosmopolitan Club. Elmhirst, an English student and Cambridge graduate, who had become a disciple of the Indian philosopher Rabindrinath Tagore, had come to Cornell to study agriculture so that he could go back to India to teach farming.

The club was in serious debt, and Elmhirst approached Dorothy Straight, widow of Willard D. Straight ’01. She was sympathetic and particularly interested in fulfilling the request in Willard Straight’s will to make Cornell “a more human place.”

Along with planning for what would eventually become Willard Straight Hall, Dorothy Straight provided an amount equal to 70 percent of the debt and $5,000 to renovate the house. Eventually she married Elmhirst and moved to England to begin a progressive school, Dartington Hall.

‘Peace and security in the near future and forever …’

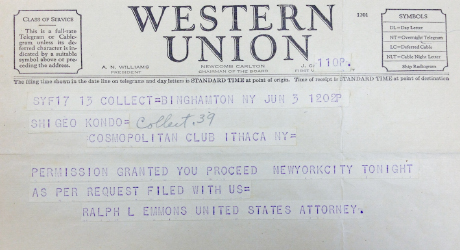

At the club’s annual Initiation Banquet on Saturday, Dec. 6, 1941, the group dined on vegetable soup and lamb chops. Student George Sutton provided an address, and then-sophomore Shigeo Kondo ’43 gave the night’s welcoming remarks. The next day, their lives changed.

While America was swept into the throes of World War II, Kondo ascended to the presidency of the Cosmopolitan Club. For the club’s annual senior Farewell Banquet, on May 10, 1942, Kondo served as toastmaster.

Kondo’s family had been classified as “enemy aliens,” and in June 1942, after Kondo’s father had quickly sold off the family’s personal belongings, Kondo and his family boarded a ship, the Gripsholm, and sailed to Japan. Kondo was conscripted into the Japanese Army despite only speaking English, having grown up in New Jersey.

(Kondo returned to the United States in 1952, and he is now a retired physician. He was elected to the Cornell University Council in October 2014 during Homecoming, and he was honored in January 2014 at the Cornell Alumni Leadership Conference in Boston with the William “Bill” Vanneman ’31 Outstanding Class Leader Award for his more than 50 years of service as an officer of the Class of 1943.)

Members of Cornell’s Cosmopolitan Club acknowledged the war, all the while keeping their own international spirits alive. Handwritten on a program from the club’s Initiation Banquet on Dec. 12, 1942, was a benediction that encompassed the sincerity of all of its members: “We who are gathered here tonight from all over the world pray that the Great Spirit who rules the Universe will guide us to the accomplishment of the finest that is in us, to the end that all nations and all peoples will be able to live in peace and security in the near future and forever.”

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe