Event looks at Islamic State group and heritage destruction

By Linda B. Glaser

The sale of looted antiquities is the second-largest source of revenue for the Islamic State group (ISIL), and it has long been a large source of funds for al-Qaida.

On March 12, faculty, students and staff gathered to discuss the recent acts of heritage destruction in northern Iraq and what, if any, response would be appropriate. The event was held in the Landscapes and Objects Laboratory in McGraw Hall in the College of Arts and Sciences.

“As developments of critical concern to Cornell scholars make the daily headlines, we felt it was an important time to gather and discuss these current affairs, to consider underlying causes, and to grapple with the difficult question of how best to respond,” said Lori Khatchadourian, assistant professor of Near Eastern studies and a Milstein Sesquicentennial Fellow.

The event began with remarks by David Powers, professor of Islamic history and law, on the intersection of Islam, iconoclasm and the Islamic State group. Members of ISIL, he explained, clearly consider themselves authentic Muslims, and their approach to images and statues is consistent with certain of the Koran’s teachings.

“Like the beheadings, the destruction of statues and images is a strategy,” said Powers. “It’s an assertion of identity that creates an ‘us vs. them’ scenario. It says that everything before Islam is barbarism.”

And while there are not many verses in the Koran that deal with statues, Islam has a strong anti-idol ideology, Powers said; Mohammed himself oversaw the destruction of more than 300 idols in the Kaaba (the location of Islam’s most sacred mosque). But in the larger context of Islamic law, the texts on which the Islamic State group bases its destruction have been neutralized by later interpretation, said Powers, but ISIL is either ignorant of this development or, as literalists, “they simply don’t want to pay attention.”

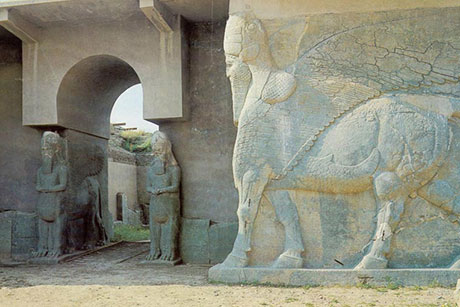

“Taking a bulldozer to Nineveh is not about iconoclasm but erasing memory,” pointed out Adam Smith, chair of anthropology. “ISIL is disenfranchising minority communities who have long been part of that world, and homogenizing the population.”

Anthropology professor Nerissa Russell, who will be teaching a course, Politics of the Past, in the fall, gave voice to a conundrum at the heart of the issue: “Given that my outrage is exactly what ISIL wants, how can we respond?”

While many ideas were explored – including working against the illegal sale of antiquities, volunteering with Saving Antiquities for Everyone and creating meaningful jobs for young men vulnerable to ISIL recruitment – many felt education was the area in which they could have the most impact. Respect for local as well as world heritage needs to be part of education at all levels, participants said.

“You win in the long run because education starts to change the values of the people involved,” noted Sturt Manning, chair of classics and director of the Cornell Institute for Archaeology and Material Studies (CIAMS).

The event was sponsored by the Near Eastern studies department and CIAMS.

Linda B. Glaser is a writer for the College of Arts and Sciences.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe