Woubshet finds poetry amid loss in the early era of AIDS

By Daniel Aloi

Growing up in Ethiopia in the early 1980s and coming to the United States as a young teenager in 1989, Dagmawi Woubshet witnessed unprecedented expressions of mourning and loss in both countries in response to the AIDS crisis.

Woubshet, associate professor of English in the College of Arts and Sciences, analyzes these cultures of mourning in “The Calendar of Loss: Race, Sexuality, and Mourning in the Early Era of AIDS,” published in March by Johns Hopkins University Press.

Chronicling some direct responses to the epidemic – elegiac and otherwise – as people lost friends, lovers and family members to the disease throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, Woubshet provides a comparative study of AIDS writings in the United States and Ethiopia.

He identifies a “poetics of compounding loss” among orphaned children in Africa and queer American artists, whose collective grief was met with social and political repression, even as they faced their own mortality as a stark and imminent reality.

“Before life-preserving AIDS drugs such as protease inhibitors became available, an entire generation of gay men were also reckoning with their own impending deaths,” Woubshet said. “The political climate was hostile to these men who were dying. There was widespread malfeasance, deafening public silence, deep fear – and initially there was no government response. The medical establishment did not take AIDS seriously.”

For a chapter titled “Archiving the Dead,” Woubshet spent more than two months at the New York Public Library reading obituaries in the gay and mainstream press.

“That concretized for me how relentless that death toll was,” he said. “For some cultural figures who were being lionized in mainstream publications, their cause of death and their sexuality was being erased. In the gay periodicals, there was a different kind of political project going on – a yearning and effort to actually embrace those elements that a mainstream publication sought to disavow. That resonated for me.”

Losing loved ones to HIV and fearing having the virus themselves, mourners were also denied the traditional ritual processes of consolation, time and closure normally afforded the bereaved, Woubshet contends. They instead responded with art and protest.

“A few communities actively had to campaign for their survival. That element of fighting to stay alive, literally mourning to survive, informed their creative artistic production,” he said. “When a doctor tells a poet, ‘You’re going to die in two months’ time,’ how do you begin to put that on the page or a canvas?”

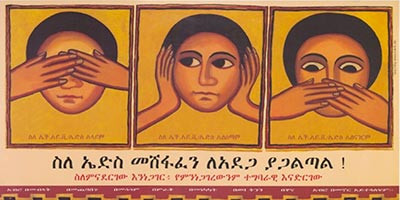

In addition to gay communities in the U.S., Woubshet also looks at “AIDS orphans in Ethiopia who’d lost their parents and were completely shunned by their communities, facing the same kind of stigma,” he said. “When their parents died they couldn’t find any other caretakers. Some were left abandoned in hospitals, some were left on the streets to fend for themselves. Not only were they bereft of parents, but the world, the entire society, had abandoned them.”

Woubshet translated from Amharic into English several letters from children to their deceased parents, written by members of Sudden Flowers, a collective of orphans in Addis Ababa ranging in age from 9 to their mid-teens.

“How do children bear loss? They can’t carry caskets,” he said. “Some of the rituals that ground us as adults, they were without. These children did not have a fixed sense of where the dead go. So they kept on talking to the parents, seeing the relationship between them as a separation that was tentative, somewhat in flux.”

“The depth of perception that these children had, that comes across in these letters, was just so profound, and profoundly moving. And they were carefully crafted,” Woubshet said. “I call them Epistles to the Dead, in part because of their literary quality.”

While writing the book, Woubshet also taught a seminar on AIDS writing and art, with class assignments utilizing Cornell’s Human Sexuality Collection. He is now at work on two book projects: “New Flower: A Memoir” and “Here Be Saints: James Baldwin’s Late Style.”

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe