Unique beak evolved with tool use in New Caledonian crow

By Pat Leonard

It was as plain as the beak on a bird’s face. Cornell ornithologist and crow expert Kevin McGowan recalls the day in the late 1990s when he first saw stuffed specimens of the New Caledonian crow.

“I remember saying to a student, ‘I don’t know what this bird does, but it does something different from any other corvid on Earth because its bill is so weird,’” said McGowan, project manager for distance learning in bird biology at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

In 2000, McGowan read a paper by Gavin Hunt, a senior research fellow at the University of Auckland, New Zealand, on tool use by these crows and he had an insight into the New Caledonian crow’s unusual beak.

Now, Hunt, McGowan and a team of scientists from Japan have quantified what makes the New Caledonian crow’s beak different and how it got that way. Their findings were published March 9 in the journal Scientific Reports.

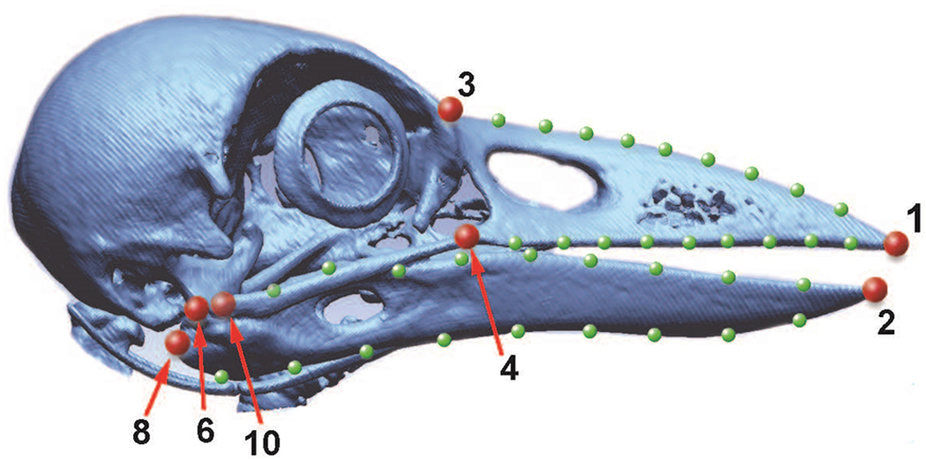

“We used shape analysis and CT [computer tomography] scanning to compare the shape and structure of the New Caledonian crow’s bill with some of its crow relatives and a woodpecker species with a similar foraging niche,” said lead author Hunt.

“This study shows that the unique bill contributes to the birds’ ability to use and probably make tools,” he said. “We argue that the beak became specialized for tool manipulation once the birds began using tools, and that this enhanced tool manipulation ability may have allowed the crows to make more complex tools.”

Such tools may range from sticks to barbed leaves or hooked twigs used to fish the crow’s favorite food from the trunk of a tree – the juicy grubs of the longhorn beetle. The birds annoy their prey by poking around the grub’s large, sensitive mandibles. When the grub grabs the stick or other tool, the bird hauls it out.

“Their bill is shorter than a regular crow’s,” McGowan said. “It’s blunter, and it doesn’t curve down like nearly all bird bills do. The lower mandible actually curves slightly up, which likely gives it the strength it needs to hold the tool. And because the bill doesn’t curve downward it brings the tool into the narrow range of the bird’s binocular vision so it can better see what it is doing.”

Birds with blunter, straighter bills were probably more adept at handling tools for foraging and over time those features evolved, McGowan said. Tool use has now become ingrained in the crow’s biology. In the case of the New Caledonian crow’s beak, you might say it’s not so much “you are what you eat,” but “you are how you eat.”

“They hold the stick tool so that it goes up along the side of their head along the length of the bill,” McGowan explains. “Apparently there are birds that favor one side of the head over the other – left-sticked or right-sticked, you could call it – it’s really cool.”

The question that cannot be answered is why the crows started using tools in the first place. It may have been a matter of chance because most birds do just fine foraging with their beaks and feet without resorting to tool-making, McGowan said.

Pat Leonard is a staff writer for the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe