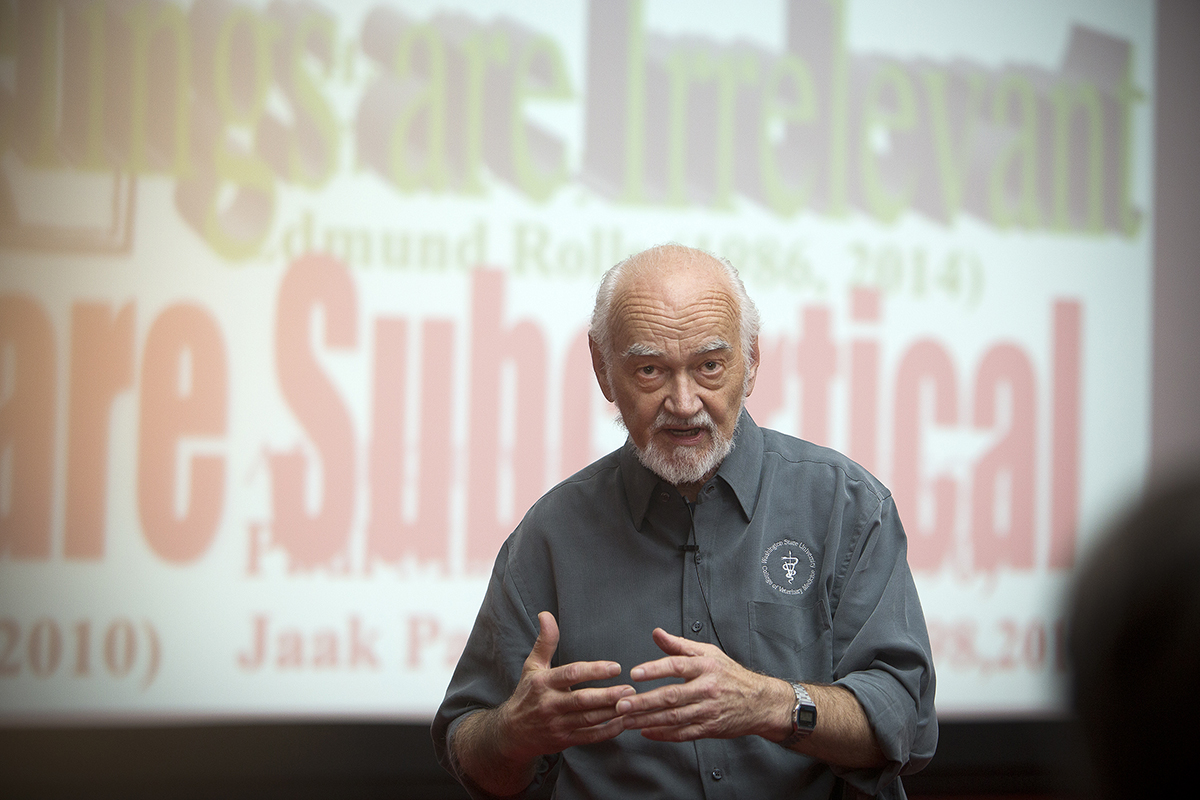

Jaak Panksepp lectures on emotions in animals, humans

By Krishna Ramanujan

“Taking the emotional feelings in animals seriously should yield more rapid understanding of human emotions,” and further work in humans could also promote development of psychiatric medicines, said Jaak Panksepp, professor of integrative psychology and neuroscience at Washington State University, speaking Oct. 24 on Cornell’s campus.

Panksepp’s statements referred to his life work to understand emotions in animals in scientific ways, and apply those findings to humans, which he discussed during his University Lecture, “The Emotional Feelings of Other (Animal) Brains: From Cross-Species Neuro-Affective Foundations to Novel Psychiatric Therapeutics.”

The publication of his 1998 book, “Affective Neuroscience: The Foundations of Human and Animal Emotions,” launched a field to identify the genetics, chemistry and brain areas where emotions take place.

In his talk, Panksepp described seven emotion systems in the brains of animals and people, including seeking (referring to enthusiasm and curiosity), lust, care and play, which all evoke positive states, and rage, fear and panic, which are associated with negative states.

His research has shown that positive emotional systems, such as seeking and play, stimulate the release of brain opioids, substances that act on opioid receptors in the brain and produce morphine-like effects. Studies of simple care, such as holding chicks, a placebo from a caring doctor or a caring therapist all show evidence of opioids being released, he said. “Positive social interaction releases opioids,” he said. “The most powerful [social interaction] we’ve found is playfulness in young animals, they release opioids all over the brain.”

At the same time, negative systems, such as panic, have an opposite effect. “Human sadness and depression are low opioid states,” he said.

Panksepp believes that compounds such as opioids and other molecules released during positive emotional states can be identified and used to effectively treat depression, anxiety and suicidal feelings.

“Which emotional system would you stimulate to reduce depression? I would say the brain reward system, or the seeking system,” he said. From studies that map brain systems involved in seeking or loss from separation from a mother, he found “depression is not a lack of pleasure; it’s a lack of enthusiasm,” he said.

In other studies, newborn chickens cried when separated from their mother, Panksepp said. But by three weeks old they showed very low separation cry. When researchers put a peptide that blocks opioids – called corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) – in the brains of these three-week-old chickens, “they cry like newborn chickens,” Panksepp said. Researchers are now studying the use of CRF antagonist (which inhibits CRF) as an anti-depressive, he said.

When studying the genetics of play, Panksepp has looked for “a possible molecule that is nonaddictive, that could facilitate a capacity for joy, but not produce joy itself,” he said. He narrowed his search to consider 17 genes and the proteins they express, out of 1,200 candidate genes. In recent work, one of those genes has led Panksepp to a molecule called GLYX-13, a peptide. “It looks like it should be a good antidepressant,” he said. In tests, low-dose treatments have shown potential for treating depression, though the system becomes blocked at higher doses, he said.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe