CU establishes a raccoon rabies-free zone in Long Island

By Stephanie Specchio

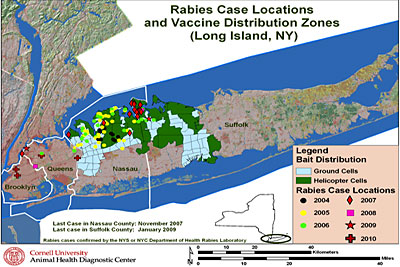

As of January this year, rabies in raccoons in Nassau and Suffolk counties on Long Island has been officially eliminated, thanks to a Cornell approach that leveraged on-the-ground and airborne tactics.

The Wildlife Oral Rabies Vaccination Program at Cornell, initiated during the mid-1990s, uses a U.S. Department of Agriculture-licensed, safe and effective liquid rabies vaccine hidden inside a small sachet that is coated with fishmeal and fish oil. Raccoons are attracted to the bait by its fishy smell; the animals puncture the baits and ingest the liquid vaccine.

Since 2006, when Cornell took over managing rabies-control efforts in Nassau and Suffolk counties, some 372,000 baits per year have been distributed, targeting populated suburban neighborhoods either via GIS-satellite-guided helicopter drops, vehicle tosses or bait stations that were developed at Cornell.

"In 2004, the New York State Department of Health identified an outbreak of raccoon rabies on Long Island and decided to take a cue from Europe, Canada and Texas, all of whom had used vaccination programs to eliminate rabies from wildlife populations," said Donald Lein, professor emeritus of population medicine and diagnostic sciences at the Animal Health Diagnostic Center at Cornell.

To keep the raccoons in Nassau and Suffolk rabies-free, however, rabid raccoons in neighboring areas must be controlled, Lein said. "At least one or two cases a year have been reported in Queens since the rabies outbreak started in Nassau County, and Brooklyn identified its first cases in 2010. Ideally, wildlife vaccination could be stopped entirely if raccoon rabies were eliminated from the entire island."

The Raboral V-RG vaccine, produced by Merial Intervet, does not include the live rabies virus and has been proven safe in more than 60 species, including dogs and cats. It takes about four weeks for an animal to find and consume the vaccine-bait and develop rabies immunity. The oral vaccine has been licensed for use in raccoons and coyotes, two significant wildlife carriers of terrestrial rabies in North America.

"The stars were aligned for success in the Long Island counties," said Laura Bigler, a Cornell wildlife biologist and program coordinator, noting that success is defined by the World Health Organization as a lack of rabies cases after two years of enhanced surveillance. "We used a higher bait density and integrated a trio of vaccination techniques that were implemented with exceptional cooperation from the Nassau and Suffolk county health departments. It is also an island environment with no skunks, a species that is known for spreading rabies and for which no effective vaccination strategy has been found in the United States. We hope to test a new, more effective vaccine in western New York later this year."

The Cornell-developed bait stations, which take advantage of a raccoon's agile front paws, are refilled periodically with bait so raccoons can vaccinate themselves through natural feeding.

"Cost-benefit analyses, completed by USDA Wildlife Services and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, have also demonstrated that financial benefits are realized through control of this fatal disease," Bigler said. "It is imperative that large-scale regional programs be supported to expand federal coordination of state-approved, wildlife rabies control efforts."

Presently, the oral rabies vaccine can only be used in programs that are approved by New York state government agencies; it is not licensed for residential purchase; baits may not be distributed outside of state-approved areas. To reduce the risk of rabies exposure, ensure that your animals are currently vaccinated and do not store trash in containers that are accessible to wildlife.

Stephanie Specchio is director of communications at the College of Veterinary Medicine.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe