Study: Honeycomb structure responsible for bacteria's extraordinary sense

By Vivek Venkataraman

Cornell researchers have peered into the complex molecular network of receptors that give one-celled organisms like bacteria the ability to sense their environment and respond to chemical changes as small as 1 part in 1,000.

Just as humans use five senses to navigate through surroundings, bacteria employ an intricate structure of thousands of receptor molecules, associated enzymes and linking proteins straddling their cell membranes that trigger responses to external chemical changes.

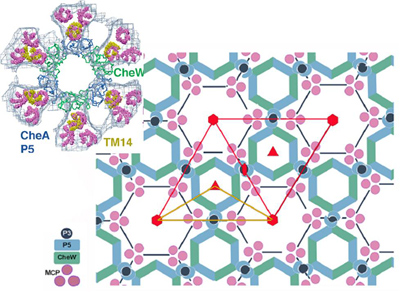

Researchers in the lab of Brian Crane, professor of chemistry and chemical biology, with collaborators in the lab of Grant Jensen at the California Institute of Technology, have mapped out the honeycomb-like hexagonal arrangement of these receptor complexes in unprecedented detail.

They report their discovery in the Feb. 20 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"The highlight of the paper is that by using a combination of [techniques], we've been able to image these complex arrays in live cells and determine how they are structured -- they are a very unique biological assembly that is conserved across nearly all classes of motile bacteria," said Crane.

The findings might have potential applications in engineering biologically inspired synthetic molecular devices to detect specific chemicals with high sensitivity over a wide dynamic range; they also could shed light on the pathogenesis of various bacterial diseases like syphilis, cholera and Lyme disease. They may also give some insight into the functioning of the human immune system, where special cells may be employing similar cooperative networks of receptors to recognize and fight against foreign antigens, Crane said.

Scientists are trying to determine how one receptor -- on detecting nutrients, oxygen or acidity, for example -- triggers communication through multiple enzymes in the complex, setting off a chain reaction. This cooperation leads to a gain or amplification in the signal that is finally communicated to the tails (flagella) of the bacterium, affecting the way they spin. Such a response allows the bacterium to move toward food sources or away from toxic environments.

The latest work takes a big step toward understanding this mechanism by demonstrating for the first time how the individual pieces of receptors, enzymes and coupling proteins fit together to generate an extended network. It builds on previous work in the Crane lab done in collaboration with Jack Freed, Cornell professor of chemistry and chemical biology.

"We were able to see how the enzymes and proteins are linked together in the complex array and also their interactions with the receptors," said Xiaoxiao Li, graduate student and joint lead author on the study.

High-resolution X-ray images of the bacterial membrane receptor complex were obtained after extraction, purification and crystallization at the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS). The scientists reconstructed the complicated molecular structure of the complex with an accuracy that is within a nanometer (a billionth of a meter). Pictures of the structure were also captured inside living cells, by first "flash-freezing" the cells and then scattering electrons off them.

The researchers deduced that trimers (groups of three) of receptor molecules are arranged at the vertices of hexagons surrounding rings of enzymes and coupling proteins. These rings linked by proteins form the backbone of the extended honeycomb-like network.

The research was funded by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the National Institutes of Health, and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

Graduate student Vivek Venkataraman is a writer intern for the Cornell Chronicle.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe