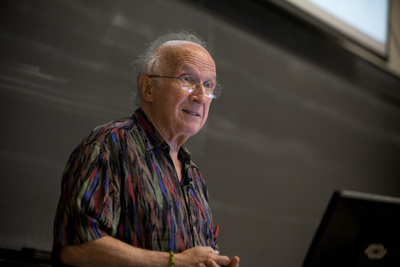

Nobel Laureate Roald Hoffmann celebrates 75th birthday

By Rebecca Harrison

When Roald Hoffmann, the Frank H.T. Rhodes Professor of Humane Letters Emeritus, received a Nobel Prize in 1981, he spoke of himself as a child from war-torn Europe, of Jewish heritage and of American dreams, said Cornell President Emeritus Frank H.T. Rhodes.

"How richly he has fulfilled that dream," said Rhodes in his video lecture as a guest speaker at a special symposium on chemistry in celebration of Hoffmann's 75th birthday, July 21-22 in Baker Laboratory, before some 160 guests.

"Alright, so ... I'm 75," began Hoffmann as he took the stage. He proceeded to present a timeline of the last 75 years from his perspective, noting important events and giving thanks to everyone who helped him along the way -- from his family members and the Ukrainian couple who hid them for 15 months during the Holocaust, to his teachers at Stuyvesant High School, his professors at Columbia and Harvard and even down to the distribution requirements he was required to take in writing and arts at Columbia, most notably those that opened his mind to the link between science and the humanities.

In finding a connection between his teaching introductory chemistry courses and his research and writing, Hoffmann said that he was then better able to communicate that he cared that his readers or audience members understood his material -- whether they were his poems, plays or his scientific papers. It became obvious that this ability to communicate, explain and teach has been a significant component of his legacy.

"I think I can say that if you've read any of [Hoffmann's] papers, that he has a very distinctive, conversational tone to his writing," said Garnet Chan, associate professor of chemistry and chemical biology, at the symposium. Chan said that he was inspired by Hoffmann's writing and work as a student in Hong Kong. "Even as a high school student I understood what was going on [in Hoffmann's papers] ... if I think of my own development [as a chemist], reading [Hoffmann's work] helped me."

"Your essays and your plays have touched such an audience that would have never had access to your life," Rhodes said in his video address. "You've said that poetry is a form of self-exposure in which you expose yourself to failure. Getting a poem published is probably more difficult in some ways than publishing a scientific paper.

"From your earliest days, you have literally done everything," Rhodes continued. "You taught first year general chem, advanced and graduate courses, distinguished graduate students; you educated a wider audience with a 26-episode PBS introduction to chemistry. You said yourself that research improves teaching, and you have turned upside down the old [model] that teaching improves research. You've argued that between the two there is a rich symbiosis. Dozens of students can testify to that relationship."

"I was born in this young, happy Jewish family, in unhappy times, in unlucky times, in the wrong place in 1937 in [Poland]," Hoffmann said. However, both physically and metaphorically, Hoffmann said his success in life was about "building bridges and making bonds."

Hoffmann, who earned his Ph.D. from Harvard in 1962, joined Cornell in 1965 as an associate professor and became a full professor in 1968. As professor emeritus, he remains an active member of the chemistry community.

In addition to lectures by Rhodes and Hoffmann, the two-day symposium also featured chemistry demonstrations from Dan Lorey and Peter Wolczanski of Cornell's Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, and lectures by Stanford's Richard Zare and MIT's Alan Lightman.

Rebecca Harrison '14 is a writer intern for the Cornell Chronicle.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe