Memory goes on trial as Cornell research suggests that children's testimony may be more reliable

The U.S. legal system has long assumed that some witnesses, such as adults, are more reliable than others, such as children.

But Cornell research suggests that children, in fact, are less likely to produce false memories and, therefore, are more likely to give accurate testimony when properly questioned.

Cornell professors of human development Valerie Reyna and Chuck Brainerd have developed mathematical models that can provide the most accurate information yet on the causes of false memories -- when a person reports what happened against an understanding of what happened.

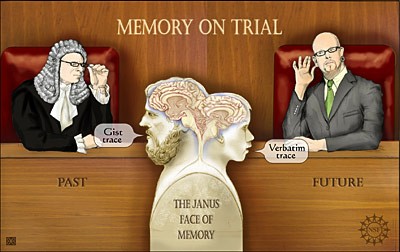

Reyna and Brainerd argue that memories are captured and recorded separately and differently in two distinct parts of the mind.

The researchers, who co-authored "The Science of False Memory" (Oxford University Press, 2005), say children depend more heavily on a part of the mind that records, "what actually happened," while adults depend more on another part of the mind that records, "the meaning of what happened." As a result, they say, adults are more susceptible to false memories, which can be extremely problematic in court cases.

Reyna's and Brainerd's research, funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF), sparked more than 30 follow-up memory studies (many also funded by NSF), which the researchers review in an upcoming issue of Psychological Bulletin.

This research shows that meaning-based memories are largely responsible for false memories, especially in adult witnesses, but in children, the ability to extract meaning from experience develops slowly, which is why children are more likely to give accurate testimony.

The finding is counterintuitive: It doesn't square with current legal tenets and may have important implications for legal proceedings.

"Because children have fewer meaning-based experience records, they are less likely to form false memories," says Reyna. "But the law assumes children are more susceptible to false memories than adults."

"Courts give witness instructions to tell the truth and nothing but the truth," says Brainerd. "This assumes witnesses will either be truthful or lie, but there is a third possibility now being recognized -- false memories."

According to Brainerd, "Things are about to change radically."

Traditional theories of memory assume a person's memories are based on event reconstruction, especially after delays of a few days, weeks or months. However, Reyna and Brainerd hypothesize (in what they call Fuzzy Trace Theory) that people store two types of experience records or memories: verbatim traces and gist traces.

Verbatim traces are memories of what actually happened. Gist traces are based on a person's understanding of what happened, or what the event meant to that person. Gist traces stimulate false memories because they store impressions of what an event meant, which can be inconsistent with what actually happened.

False memories can be identified when witnesses accurately describe what they remember but those memories are proven false based on other unimpeachable facts.

"When gist traces are especially strong, they can produce phantom recollections -- that is, illusory, vivid recollections of things that did not happen, such as remembering a robber brandished a weapon and made threatening statements," says Reyna.

Brainerd argues that because witness testimony is the primary evidence in criminal prosecutions, false memories are a dominant reason for convictions of innocent people.

In child abuse cases, where the law gives the benefit of the doubt to adult testimony, the results can be even more disconcerting. "Failure to recognize differences in how adults and children produce memory unfairly tilts the U.S. legal system against child witnesses," says Reyna.

The researchers say their transformative "two-mind" memory approach can reduce the number of false memories in court cases and give more validity to children's testimony.

They have developed several associated mathematical models that test memory and can be used to predict memory outcomes in both adults and children.

The models have been used to determine ways in which attorneys, investigators, law enforcement officials and others can ask questions to help people access verbatim memories while suppressing false memories. The researchers say using neutral prompts to cue witnesses can help them remember what actually happened.

Reyna and Brainerd also say returning a witness to the scene of an event in a highly neutral way can cue verbatim memories and help the legal process.

This article is abridged from the National Science Foundation Web site.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe