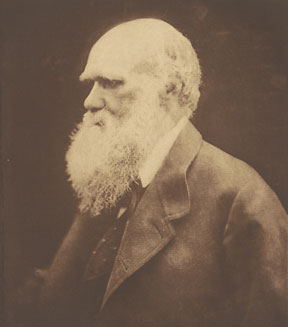

Charles Darwin exhibits show the mind of a naturalist

By Sheila Ann Dean

Charles Darwin's gift as a naturalist is often overshadowed by the continuing impact of his ideas. Yet his discovery of natural selection and the mountain of evidence for evolution presented in "On the Origin of Species" could not have emerged without his skills as a meticulous observer of nature. Along with his insatiable curiosity about almost any form of life, Darwin the naturalist continued to gather material in support of evolution for 22 years after he published his famous book in 1859.

The collaborative exhibition "Charles Darwin: After the Origin," displayed at the Carl A. Kroch Library at Cornell and Ithaca's Museum of the Earth, celebrates Darwin's astoundingly diverse research during this time, and the images on this page are selected from those studies. His botanical work was perhaps the most prolific, involving insectivorous plants, insect and flower co-adaptation, movement in plants and hybridization.

Darwin also studied artificial selection by investigating the variation of domesticated animals, including dogs, sheep, chickens, pigs and pigeons. His fascination with variation led him to closely study human evolution and provide evidence for descent from an "apelike progenitor." Facial expressions provided further support that humans evolved from other animals, and his "The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals" was one of the first scientific books to rely on photography. Darwin's work on human descent also included a massive amount of research on sexual selection, and he was the first to describe the process in detail. Toward the end of his life, his examination of earthworms and the formation of soil returned him to some of the geological pursuits that had occupied him as a younger man.

In addition to an ever-present awareness of the importance of evolution to any biological query (a consciousness that would be useful to educators today), Darwin also often expressed a particular awe of nature.

In 1871, he wrote in "The Descent of Man": "Unless we willfully close our eyes, we may, with our present knowledge, approximately recognize our parentage; nor need we feel ashamed of it. The most humble organism is something much higher than the inorganic dust under our feet; and no one with an unbiased mind can study any living creature, however humble, without being struck with enthusiasm at its marvelous structure and properties."

Sheila Ann Dean is a visiting curator for Cornell University Library and a visiting scholar in the Department of Science and Technology Studies.

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe