Scott Emr to lead biology institute at Cornell

By Krishna Ramanujan

Scott Emr approaches science first by asking a basic question. Then comes the hard work of finding an answer. A highly respected biologist who has been hired as the Frank H.T. Rhodes Class of '56 endowed director of a new Institute of Cell and Molecular Biology -- the cornerstone of the $650 million New Life Sciences Initiative -- Emr has used this scientific method to uncover the molecular details of essential processes that occur in all cells.

Emr (pronounced Emmer), currently a University of California-San Diego School of Medicine professor of cellular and molecular medicine and an investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, will begin his Cornell appointment in February 2007.

Emr's answers to the question of how proteins get in and out of cells, a process called cell membrane trafficking, are so fundamental that the work is found in college biology textbooks. It has given other scientists many new pathways and targets for cutting-edge research on virology, HIV-AIDS, cancer, immunology, development and neurobiology.

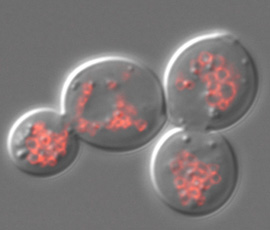

His research explains the inner workings of such basic processes as endocytosis, in which proteins attach to receptors on a cell's surface and become encapsulated in vesicles as they forge into the cell's body. The proteins are delivered to areas within the cells where they activate basic cellular processes. Similarly, in the process of secretion, such proteins as insulin are produced within cells and carried by vesicles to the cell's surface, where the vesicle fuses with the cell's membrane and the proteins are released outside the cell.

Emr has used genetics, specifically the genetics of single-celled yeast, to identify the specific molecular pathways that drive these basic processes. Emr said that yeast provides an excellent model for the fundamental biology of all cells.

"Yeast have 6,000 genes (humans have on the order of 30,000 genes), but of those 6,000, most are also represented in the human genome," said Emr, who was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2004. "So yeast is a model for the core cell biological apparatus contained in all eukaryotic cells [containing DNA] -- from yeast to humans."

At Cornell, Emr hopes to again use yeast cells to answer questions of how neurons in the brain can last a lifetime -- people die with the same functioning neurons with which they were born. Neuronal cells have mechanisms for replacing and ridding themselves of inactive or damaged proteins, much like clearing out junk and garbage from a house. Emr will seek to better understand these "garbage clean-up mechanisms," which when impaired can lead to some 40 known inherited neuronal and degenerative diseases, like Tay-Sachs disease.

Emr earned his doctorate in microbiology and molecular genetics at Harvard University in 1981, but his interest in biology began in elementary school when he spent hours watching ants building paths in the yard at his grandparents' house.

Soon after, he bred fish, which led to experiments on them in high school. But, he said, a college course at the University of Rhode Island (where he earned his B.S. in biology in 1976) on bacterial genetics changed his life forever. He recalls being "captivated" by the subject once he understood how genes related to function, and how a single mutation in a bacterial gene can cause the organism to lose its ability to chemically sense its environment.

"By one mutation in one gene you make a huge fundamental advance in understanding the mechanism," he said.

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe