In forthright speech, Rawlings calls on Cornell to address 'invasion of science by intelligent design'

By Susan Lang

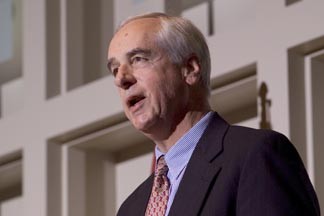

Delivering his first State of the University address since taking office as interim president of Cornell University following the resignation of Jeffrey Lehman in June, Hunter Rawlings called on Cornellians to address head-on the complex and cultural – not scientific, he asserted – issues of where the religiously based "intelligent design" (or I.D.), controversy belongs, both inside and outside the classroom and university.

In a forthright speech at the university's annual Trustee/Council Weekend Oct. 21 in Statler Auditorium, Rawlings also paid tribute to Cornell's founding fathers for firmly committing to a nonsectarian institution.

Rawlings said that some polls show that 40 percent of Americans believe that creationism should be taught instead of evolution in public schools, and about half of the Cornell students in the large course on evolution for nonmajors agree that "some sort of 'purpose' [is] informing the process through which life develops." However, Rawlings said, "I.D. is not valid as science. … I.D. is a subjective concept. … a religious belief masquerading as a secular idea. It is neither clearly identified as a proposition of faith nor supported by other rationally based arguments." Advocates of I.D. voice a creationist argument that some features of the natural world are so "irreducibly complex" that they must have required a creator, or an "intelligent designer."

I.D. is, he said, "a matter of great significance to Cornell and to this country as a whole … a matter … so urgent that I felt it imperative to take it on for this State of the University address." The packed auditorium gave Rawlings a lengthy standing ovation at the conclusion of his address.

"I am convinced that the political movement seeking to inject religion into state policy and our schools is serious enough to require our collective time and attention," he said. As such, he asked that Cornell's three task forces -- on the life sciences, on digital information and on sustainability -- consider how to confront such questions as "how to separate information from knowledge and knowledge from ideology; how to understand and address the ethical dilemmas and anxieties that scientific discovery has produced; and how to assess the influence of secular humanism on culture and society."

He said that Cornell, which some refer to as the world's land-grant university, is in a unique position to bring humanists, social scientists and scientists together to "venture outside the campus to help the American public sort through these complex issues. I ask them to help a wide audience understand what kinds of theories, arguments and conclusions deserve a place in the academy -- and why it isn't always a good idea to 'teach the controversies.' When professors tend only to their own disciplinary gardens, public discourse is seriously undernourished," he said.

In his address, Rawlings first reviewed how the I.D. issue is playing out across the country, with disputes about evolution making news in at least 20 states and numerous school districts. He then recounted the controversy historically, with Darwin publishing his groundbreaking book, "On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection," in 1860; the 1925 Scopes trial that deterred anti-evolution legislation pending in 16 states at the time; and the 1987 Supreme Court ruling that ruled as invalid Louisiana's "Creationism Act" that would have forbade teaching evolution in public schools. Now the controversy is back full throttle in a highly polarized nation, Rawlings said, challenging again what is taught in schools and universities.

Rawlings then reviewed how Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell's first president, were definitive about the issue when they created the first "American" university. Rawlings quoted White as writing that the institution "should be under the control of no political party and of no single religious sect." Rawlings then quoted from a letter Ezra Cornell had placed in Sage Hall's cornerstone in 1873, and unearthed just a few years ago, that warned that the only danger the university's founder could foresee to the "friends of education, and by all lovers of true liberty is that which may arise from sectarian strife. From these halls, sectarianism must be forever excluded." The letter stressed, though, that students should be free to worship as they pleased.

Rawlings concluded that in the spirit of being one of the world's "great global research universities," Cornell helped to launch Voyager I – which, as it prepares to leave the solar system for the "vast unknown of the interstellar medium," is the most distant object created by humans in the universe. The spacecraft, he said, is the result not only of scientists' scientific method and experimentation but also of imagination and creativity. "They inspire in us the emotions we associate with both religion and science: awe, wonder, curiosity and the desire to know more."

Rawlings ended his address by saying, Cornell "is also a place that has nurtured great intellectual leaders who have not only made landmark contributions to their disciplines, but who are willing to speak out, frequently and forcefully, about the obligation of the academy to pursue knowledge and truth unfettered by political or religious dogma. Cornellians who do so will be acting in the great tradition of Cornell's founders, Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White."

Said Cornell trustee Robert Harrison '76 after the standing ovation: "I think that was the most powerful speech I have heard from a president of the university since I was an undergraduate. I think it is in the tradition of taking Cornell back to its roots because it uses the platform of the presidency and this great university to engage in a civic conversation, a discourse which affects major issues."

"Very stimulating," said trustee David Croll '70. Trustee Karen Rupert Keating '76, agreed: "Highly thought provoking … bold and on an appropriate topic of national import."

Peter Meinig '61, BME '62, chair of the Cornell Board of Trustees, who introduced Rawlings, told the audience that the board's search committee already has an "impressive list of interested candidates" to succeed Rawlings when the interim president returns to teaching the classics next year.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe