Cornell's solar house takes second place in national competition

After a week of tense and intense judging in the 2005 Solar Decathlon solar-house design contest, the Cornell University team took second place to defending champion University of Colorado in the final rankings.

California Polytechnic State University (Cal Poly) was third, and Virginia Technical Institute and State University (Virginia Tech) placed fourth. Cornell trailed Colorado by about 28 points in the final results. But the Cornellians beat out Cal Poly by about 17 points.

The University of Colorado won the first Solar Decathlon in 2002. This was Cornell's first entry in the competition, and it was the only solar-powered house from an Ivy League school.

"It was a lot of hard work but it feels great to come in second; it makes it feel like it was worth all the time and effort," said Larissa Kaplan, AAP '06, one of the Cornell Solar Decathlon project leaders. "And because it wasn't sunny all week, it made for a much more strategic competition - not just a display of the houses' capabilities. It really showed how our house could survive in conditions that aren't ideal. We designed a house that could be used in Ithaca."

There were 18 entries gracing the capital's National Mall for the U.S. Department of Energy's international Solar Decathlon competition. Teams were judged in 10 areas, including architecture, dwelling, documentation, comfort zone, appliances, hot water, lighting, energy balance, communications and documentation. The teams also had to provide enough solar energy to power a small car.

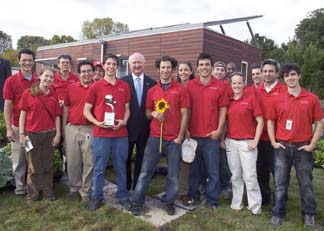

Cornell's team consists of about 50 undergraduate students from six of the seven undergraduate colleges at Cornell -- about 40 percent of them engineering majors, 40 percent architecture majors, 10 percent business or economics majors and 10 percent with other majors -- as well as a handful of graduate students. Some of the undergraduates spent two years designing and building the solar home.

Engineering Professor Zellman Warhaft, who has been serving as the project's adviser from the beginning, was in Washington for the final judging. He said, "In my 25 years on the faculty, this is one of the most thrilling projects I've ever seen. This group is a wonderful diversity of gender and ethnicity."

Warhaft praised the Cornell house by saying, "It has modernity, but it is not absurdly avant-garde. The other [17] Solar Decathlon teams focused on their own house, while Cornell integrated the landscape into the house's design. The garden is lovely and functional."

As the home was being prepared for the contest, tourists passed the Cornell solar house and admired the colorful, landscaped garden. Cornell students Lucas Wooster, Marc Miller and Alex Lavallo grew more than 1,500 edible plants -- like peppers, lettuce and herbs -- for the home's landscaping. It took four Penske rental trucks to bring all the plants from Ithaca. The Washington Times newspaper called Cornell's landscape the best garden in the Solar Decathlon.

In 2003 10 undergraduates submitted a proposal to the DOE, which accepted the proposal and gave the team $5,000 in seed money. The team recruited dozens of students to participate and raised about $65,000 in cash from about 15 individuals, mostly alumni, and another $120,000 in product donations from about two dozen companies. The entirely student-run project also has received funding from Cornell's College of Engineering, College of Architecture, Art and Planning (AAP) and College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. The entire Cornell project cost about $350,000, including the cost of donated items.

The 16-by-40-foot house consists of a living room/study/kitchen, bedroom and bathroom, numerous nooks and crannies for storage and a large array of photovoltaic (PV) cells, an evacuated solar tube collector and a large battery bank to collect and store enough energy to run all the appliances in the house as well as an electrically powered car. All the house's systems are controlled by a touch-screen remote.

"The experience has been great, though we're exhausted," said Ben Uyeda, AAP '05, a project leader and a visiting lecturer in architecture who has worked on the project from its beginnings when he was an undergrad. He has been in Washington for three weeks now and is helping to pack the house up to bring back to Ithaca. "It's nice to be number two, but we were less interested in the gamemanship or the Web site -- which allowed Colorado to win -- than we were in building the house we wanted to build." And that was a home, or set of home designs actually, that could be mass produced.

Uyeda said the house will soon be set up on the Cornell campus, and programs will begin to educate the community about sustainable living systems and strategies. The team is continuing to investigate how to proceed to commercialize the design.

"We designed alternate versions, such as one for the cold winters back here in Ithaca, but made sure each complied with HUD guidelines for manufactured housing," pointed out architecture student Stephanie Horowitz, AAP '05, a project leader. The team's goal was to create an affordable house that could sell for $50,000 to $100,000.

The Cornell house features a custom-designed energy recovery ventilator (ERV). ERVs are very effective at reducing the additional energy load for ventilation. To maintain healthy indoor air quality, adequate ventilation is necessary. The problem with good ventilation, however, is that it takes a lot of energy to heat cold, winter air or to cool and dehumidify hot, humid summer air.

The key component of Cornell's ERV is a rotary wheel composed of silica gel -- the same material used in the little packets found inside food and other packaging. In summer, for example, the silica gel absorbs humidity from the fresh air intake before it reaches the air handler. It is then wheeled around to be regenerated, transferring the humidity to the exhaust along with extracted heat. This preconditioning can dramatically reduce the energy consumption of the heating and cooling system.

Of all the innovative technologies in the home, "I am most proud of the ERV and the control system we developed for it," says Tim Fu, mechanical engineering grad student.

Control systems are another technical highlight of the Cornell entry, with systems designed to make it "very much a smart house," says Uyeda. Everything is controlled automatically but also can be adjusted by the occupants, with manual-override touch-screen controls in several places. Heating and cooling beyond that provided by the ERV is by forced air from an electric heat pump. An evacuated-tube solar thermal system provides domestic hot water. Power for the heat pump and home electrical needs comes from a set of crystalline-silicon PV panels. General Electric donated all the PV panels and most of the home appliances - all Energy Star - under a full sponsorship arrangement for the Cornell Decathlon home.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe